Within the inner circle of the War Memorial, you’ll find the names of 33 Amherst men, from the classes of 1899 to 1920, who lost their lives in “the war to end all wars.” Here are sketches of three:

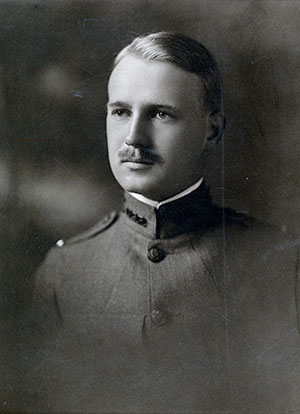

Wallace Minot Leonard Jr. ’16

Wallace Minot Leonard Jr. ’16 was one of them. He’d grown up in Newton, Mass., and at Amherst had been managing editor of The Student, worked on the Olio and was captain of the gymnastics team. In his senior year, his classmates chose him to give the prestigious “Grove Oration” speech. (Calvin Coolidge had been so honored in his own class.)

First Lt. Leonard married Dorothy MacLure in 1917, just before shipping out with the U.S. Marines. He was assigned to the 6th Regiment, 79th company—and would become the most decorated Amherst man to die in World War I, receiving the rare Distinguished Service Cross for heroism, as well as the French Croix de Guerre.

This was because of what happened on June 6, 1918. On a day of fierce fighting, Leonard was ordered to lead his 43 men to attack a nest of German machine guns in the town of Bouresches near Belleau Wood. They crawled a thousand yards of open field under unremitting enemy fire. By the time they reached the gun emplacement, on a rooftop in the town, Leonard’s uniform was pierced by bullets in three places but, incredibly, he was unharmed.

After rushing up the stairs, the men—only five now left—killed the German gunners and captured seven enemy machine guns “which had been playing its leaden stream like a garden hose upon the Americans,” according to one news account. “I don’t recall much that happened,” Leonard told a friend. “We spent most of our time hanging onto Mother Earth.”

In the Frost archives, you can read his charismatic letters home, including one to a Quaker childhood friend who asked what he thinks of pacifism. Leonard heatedly describes German atrocities against civilians and long lines of war refugees, and says this: “No sane man could possibly be a pacifist having seen what I have seen.”

After the battle, Leonard was sent to train soldiers at Ohio’s Camp Sherman. Six months after miraculously surviving Belleau Wood, he died there of pneumonia.

It was “a kind of ironic blow not uncommon during the Great War,” to quote a recollection written about Leonard. Indeed, upwards of a third of those alumni who died in World War I succumbed to germs, not bullets, mostly because of the flu pandemic of 1918.

Eight months after Leonard’s death, his wife gave birth to their daughter.

Harry Albert Bullock ’99

This Royalston, Mass. native, grandson of Massachusetts Gov. Alexander Hamilton Bullock, was indefatigable at this kind of thing. He’d been an investigative reporter at The New York Times, breaking complex stories on railroad scandals and landing an exclusive with the reclusive Union Pacific magnate E.H. Harriman. Impressed, the directors of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit authority hired Bullock away to tackle logistics for their 2 million subway riders. At the BRT, he founded a bureau of public safety, plus a medical bureau that gave free treatment to each of the authority’s 15,000 employees.

“Work to him was always dramatic,” as it said in B.R.T. Monthly. “Even the drab and statistical he wrestled with joyously.”

Capt. Bullock was too old to see combat—he was 39 when he went to France, having used his vacation time to attend New York’s Plattsburg Officer Training Camp. So the army deployed him to its Quartermaster Reserve Corps, where he oversaw the transport of troops and supplies for the First Division.

On May 30, 1918, just after the First had taken the town of Cantigny, he was meeting with several other division leaders to hammer out the water-in-gas-tanks details. They sat inside a brick villa, five miles back from the front lines. Suddenly, the Germans launched a counter attack, and fighter planes swooped above. One dropped an aerial bomb, which split the villa in half: Bullock and four others were killed instantly.

The Times ran an appreciation of their former reporter. He enriched his profession, it said, “by directing with energy and unfaltering courage, and his keen and highly trained intellect, toward the promotion of the public good.”

Daniel Stevenson Smart ’14

Daniel Stevenson Smart ’14 grew up in Cambridge, N.Y., near Glens Falls, where his father, John H. Smart ’68, led the local Presbyterian church. At Amherst, Daniel played baseball and ran track and was a member of the Christian Association Cabinet; after graduation, he attended Princeton Theological Seminary and was ordained one month before sailing to France.

Smart was commissioned a 1st lieutenant and got assigned to the 328th Infantry as a chaplain. For months, he buoyed the troops, calmed the wounded and performed burials in the various denominations of the deceased.

“He made Christ seem very real,” said one of Smart’s compatriots.

On Oct. 15, 1918, in a break in fighting near San Juvin and Sommerance, Lt. Smart and a Red Cross worker were bringing tobacco and chocolate to the troops at the front when they found some men recently killed in action. They began to ready them for burial and, as Smart pulled out his prayer book, a shell exploded alongside. The Red Cross worker died right then, but Smart seemed only slightly wounded. He was carried on a stretcher to Hospital #14 behind the lines. The head chaplain wrote to Smart’s sister about what happened next:

“Your brother was conscious when he reached the hospital and his smile was still with him. While he was waiting to be taken into the dressing room he laughed and comforted another lad supposed to be more seriously wounded than he.”

Smart died on the X-ray table: the shell had severed his kidneys. The hospital chaplain reached into Smart’s pocket, took out the prayer book there and paged to the Presbyterian section. Then he read the brave young man the rites of his faith.