The night she spoke, fresh snow feathered every branch, and the wind quelled under a half moon. It seems right to honor the natural world first, because that’s what Lisa Brooks does throughout her new book, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War.

In fact, it opens in the spring of 1623 “as the first leaves of sassafras and strawberry emerged in the Wampanoag country.” And the title heralds the Indigenous kind of kinship, encompassing not just humans but animals, trees, rocks, all the gifts of the earth.

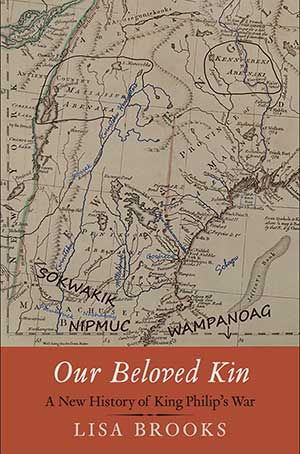

King Philip’s War, which began in 1675, has been viewed as the last major effort by the Native Americans of southern New England to drive out the English settlers. As trade partnerships collapsed and the colonists aggressively encroached on Native territories, the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, Pocumtuck and Narragansett tribes led an uprising.

“King Philip” was the English name given to the Wampanoag sachem Metacom, a nod to Philip of Macedon, son of Alexander the Great. For her book, which also features a digital companion, Brooks found stories via many Indigenous sources, such as land deeds, historical accounts and petitions. As she writes in the book: “These stories reverse the narrative of absence and reveal the persistence of Indigenous adaptation and survival.”

One audience member asked if Brooks’ view of Metacom had changed. “He became smaller,” she said. “It became very clear this was not Philip’s war.” He was involved in the first strikes, Brooks noted, but was just one of many leaders within the alliance.

Another leader, though, has not gotten her due. That would be Weetamoo, the sister-in-law of Metacom and the suankskwa, or “rock woman” female leader of the Pocasset branch of the Wampanoags.

In previous histories of King Philip’s War, Weetamoo “is often relegated to a minor role,” Brooks said. “But her diplomacy and her protection of hundreds of people is astounding.” She finessed deeds to protect tribal land and, when the war began, helped her people find sanctuary in the sprawling swamps of central Massachusetts—which the English feared to enter. In the Algonquian languages, the word for “peace” and “swamp” are related.

To research the book, Brooks also consulted with Native American language leaders, and canoed and bushwhacked through the places it took place. “I like to get muddy,” as she told the GCC audience with a smile.

In the book, Brooks also focuses on the famous narrative of colonist Mary Rowlandson during King Philip’s War. She was taken captive by a Narragansett man during a Nipmuc raid of Rowlandson’s town of Lancaster, Mass., which lay in Nipmuc land. That man gifted Rowlandson to Weetamoo at Menimesit, a sanctuary for many communities. Rowlandson later complained that Weetamoo didn’t give her enough to eat. In reality, Weetamoo was in charge of evenly allotting food to all in a time of scarcity, and didn’t want to privilege one person over another.

Nonetheless, Brooks repurposed Rowlandson’s chronicle to help pinpoint the geography of King Philip’s War, and also to highlight another crucial Native actor: James Printer, a Christian Nipmuc fluent in English, recruited to work at the Harvard Press as a translator and printer, and the sole person who could set type in Algonquian. He printed Rowlandson’s narrative, and helped negotiate between the colonists and the tribes. “Printer made a major contribution that is not recognized,” said Brooks.

As Brooks said of Weetamoo, Printer and the Indigenous people she studied: “No matter where they were, they were trying to protect their kin no matter what.”

That thought lingered as the crowd left the lecture hall for the parking lot, which sits in Pocumtuck territory, as snow fell in the night sky.