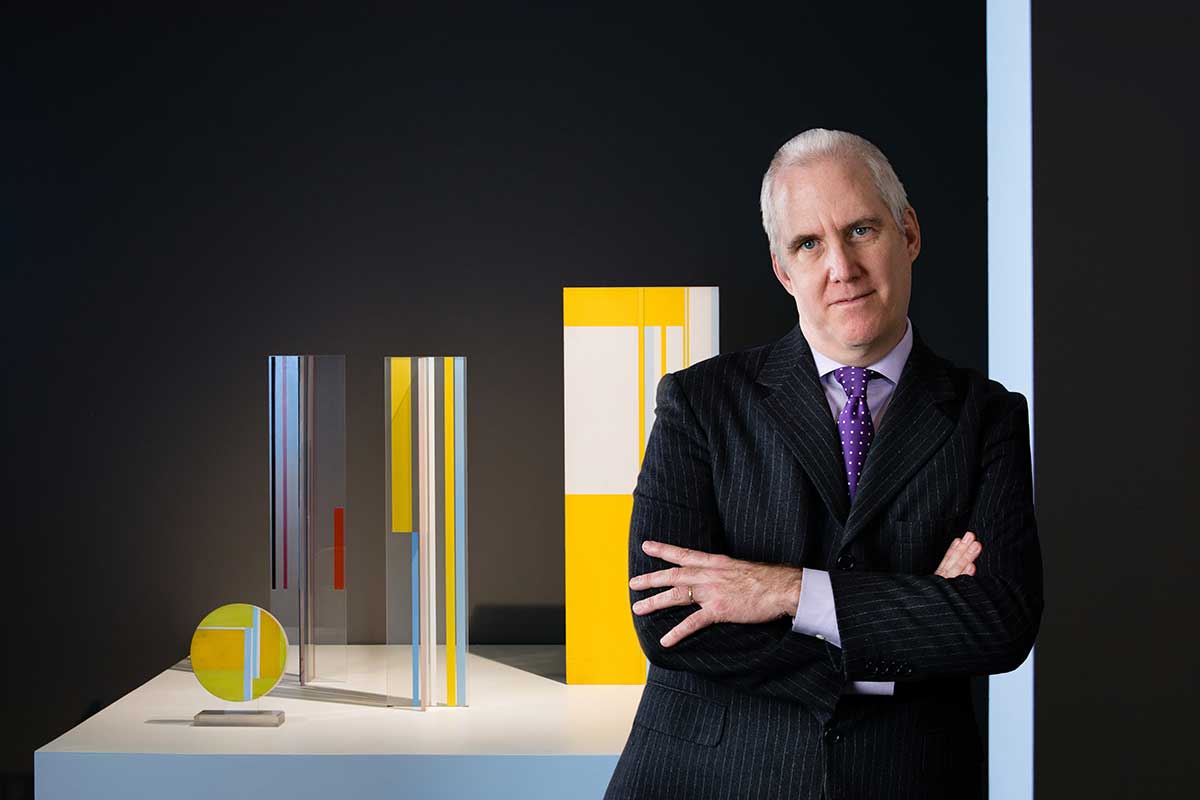

David E. Little, the director and chief curator of the Mead Art Museum since 2015, Skypes a lot. And when he’s talking face-to-face onscreen with collectors, donors, art dealers and more, he likes the wall they see behind him to display some dynamic art, liberated on a rotating basis from the Mead’s collection.

The October day we met (in person) in his office, the Skype-eye-level work was a cornflower-colored calligraphic painting called I Like Blue, by Ulfert S. Wilke (1907–1987). In 2016 it was part of the Mead Reimagined show, which featured new works in the collection, most of them contemporary.

Contemporary art is a rich and loaded topic that Little knows a lot about. Before arriving at the Mead, he was head and curator of the Department of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art; sometime before that, he was the director of adult and academic programs at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Museumgoers can find contemporary art hard to grasp, and museums can find it hard to collect: present-day art by known artists is wildly expensive, even for the big museums, let alone smaller college museums like the Mead.

But in the last decade, the Mead has steadily bolstered its contemporary collection. In 2008, the Trinkett Clark Memorial Student Acquisition Fund was created to honor the Mead’s former curator of American art, who died in 2006. Since he arrived, Little has bought some 300 pieces of contemporary art for the College. And in August 2019, the Mead announced that it received a gift of more than 170 contemporary artworks from an anonymous donor.

To celebrate this depth and momentum, Little has curated and mounted a new show. Called Starting Something New: Recent Contemporary Art Acquisitions and Gifts, it opened on Sept. 10, 2019, and will run through July 26, 2020.

The exhibition’s roster of global artists boasts familiar names—David Hockney, Cindy Sherman and Mark Bradford—and some remarkable emergent artists, including Heather Agyepong, Kapwani Kiwanga and Analia Saban.

As we sat to talk, my eyes dazzled by I Like Blue, I asked Little about the College and its evolving commitment to contemporary art.