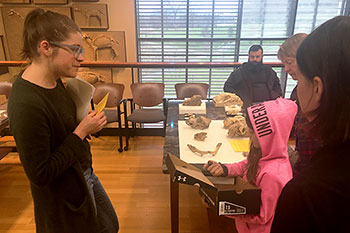

Since 2014, the Beneski Museum of Natural History has hosted Identify It Day, an annual event where the public is invited to bring in rocks, bones and other mysterious objects, and present them to our experts to identify.

“A lot of times in museums you get people from the public who come in and say, ‘Hey, I found something and I don't know what it is. Can I come in sometime?’” said Hayley Singleton, head of collections and operations at the Beneski. Staff landed on the idea of simply opening their doors for an afternoon in the fall and having geologists and other science faculty examine their finds.

David Jones, associate professor of geology, crouched down to talk with 9-year-old Izabella Aliengena of Monson, Mass., about her family’s collection of possible fossils, found on a riverbank during a vacation in Willet, N.Y. One of the rocks indeed showed evidence of underwater life, but not having to do with rivers, Jones told her.

“When these little creatures were alive, they were actually living in an ocean that covered up most of New York state,” he said. “These are little animals called brachiopods. They kind of look a little bit like clams, but they’re actually a completely different kind of animal.”

He then showed Izabella how to use a geologist’s hand lens to get an extra-detailed look at the newborn brachiopods in her fossil.

“Whoa,” she remarked.

Even if the Beneski team can’t identify the fossil or, more likely, it doesn’t turn out to be what its owner hoped, “I always try to leave people with a story,” said Professor of Geology Peter Crowley, who got the event started back when he was the director of the museum.

“There are also lots of non-dinosaur footprints that come in,” Crowley added, noting that some collectors can mistake bone-shaped stones or foot-shaped depressions in other kinds of rock for actual tracks or fossils, preserved in sedimentary rocks formed from layers of sand or mud.

“Still, we try to leave people with the story of how that thing may have formed. And if it’s a rock, it has a complicated history,” he said.