When Harold Wade Jr. ’68 wrote Black Men of Amherst, he knew he likely missed including some of the earliest Black alumni, since he didn’t have access to the earliest student information. As the College enters its Bicentennial, the archivists at Frost have been working to digitize the Amherst College Albums, which acted as proto-yearbooks from 1853 to 1909.

In the process, they learned about people whom Wade never knew about.

Mike Kelly, head of Archives & Special Collections at Amherst, recently wrote a blog post about these men. He found some tantalizing preliminary information—and we decided to dig in further here.

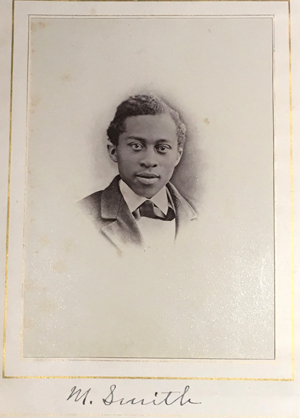

Madison Smith, Class of 1877

Picture torrential rains. Thousands of boots stuck in a vast sump of mud. “It was the damnedest marching I ever saw,” said Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. His 60,000 Union troops and 2,500 wagons had just reached the southern edge of North Carolina. It was March 8, 1865. They were five months into Sherman’s march north from Atlanta, breaking the Confederacy into pieces as they went. They were also, to quote a popular song, making “a thoroughfare for freedom and her train.”

All this may explain why Smith’s “case excited much sympathy among the people of the town,” as Arthur Haydn Pearson, Amherst class of 1877, later wrote of his friend. A local carriage manufacturer and Congregationalist minister provided employment and education. In several years, Smith, who had an unspecified disease, had qualified for Phillips Andover.

Smith seems to have thrived at Andover. In their archives, he is listed as an executive in both the school’s prestigious Philomathean literary society and the Society of Inquiry. He was an officer with the Class Nines, an early baseball club. He had a good class rank and won prizes for his original compositions.

In 2019, Phillips Andover launched the Madison Smith Presentation Series, in which a faculty member engages the community on an issue. One wonders what Smith would think of its first presentation. The title is “Perceptions of Color: Seeing and Being in the Racialized World.”

At this point, it must be said that most of what we know of Smith comes through 19th-century white sources. We know nothing from Smith directly, and almost nothing about his time at the College. Pearson said Smith made many friends here, and when his disease returned “there was no lack of those who were pleased to wait upon him.”

Smith died in 1875, the summer after his sophomore year, a decade into his freedom, To honor him now, it may help to learn one more detail from his life at Andover: Madison Smith was an alto in the choir and at commencement, in 1873, he was chosen to perform several ballads. We don’t know what they were.

But we know he lifted his voice.

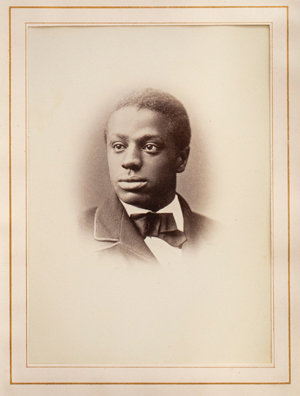

Charles Sumner Wilson, Class of 1877

This story begins with great promise and ends with great pain.

Charles Sumner Wilson, class of 1877, was born in 1853 in Salem, Mass., the third son of parents who fought—and sacrificed—for the rights of Black people.

Rebecca Eldredge Wilson, a poet and seamstress born in Rhode Island, was an active member in the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, the nation’s first female abolitionist organization, founded in 1832 by free Black women in Massachusetts.

The Wilsons named their son after Charles Sumner, the abolitionist Bay State U.S. senator who, in 1856, was caned nearly to death by a pro-slavery Southern congressman. During Wilson’s life, much was made of this moniker. A “euphonious and highly honorable cognomen,” noted one item in the Black press.

Indeed, Wilson was all over the news in 1870. This is because, after graduating at the top of his high school class in Salem, he became the first Black man in history to be nominated, by a congressman, for admittance to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Wrote one reporter: “[Rebecca Wilson’s] deep interest in the Anti-Slavery movement together with the service of her husband as a soldier, renders the appointment of her son a gratifying testimony to the common people, the unexpected but deserved reward for loyalty to human rights.”

But Wilson never attended West Point.

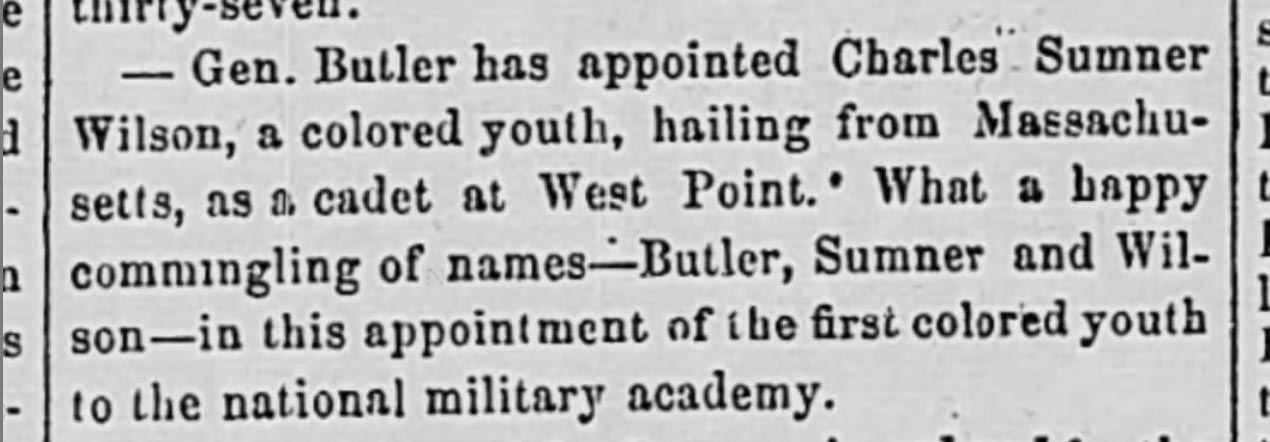

The Intelligencer, Anderson, S.C., March 17, 1870. “Gen. Butler has appointed Charles Sumner Wilson, a colored youth, hailing from Massachusetts, as a cadet at West Point. What a happy commingling of names—Butler, Sumner and Wilson—in this appointment of the first colored youth to the national military academy.”

His nominator was U.S. Rep. Benjamin Butler (R-Mass.), perhaps the war’s most radical Republican general. Butler wanted to make a bold statement to his opponents and also to curry favor with his Black constituency. But you must be 17 to enter West Point on the first day of the next term, and Wilson was a few months short, a fact Butler surely knew. Was the nomination just for show?

So Wilson was passed over—but he created a path for others. Within months, other legislators put forth another Black candidate, and then the first Native American candidate.

Because he does not go to West Point, Wilson looked elsewhere for his education. He attended Amherst from 1873 to 1875 before graduating from Tufts in 1878. In 1880, a news item said that Wilson passed the bar—the first Black man ever admitted to the Essex County bar. He had a law office in Boston and in Salem, and specialized in collections.

The story turns here: In 1891, the Boston Post ran a disturbing—and arguably dubious—article stating that Wilson had “shown signs of insanity … and again became violently insane” by threatening the Salem police marshal. Wilson was said to have “the delusion that that marshal owed him some money” and had started a petition to bring a lawsuit for recompense. Doctors were called in to determine his sanity.

There was nothing about Charles Sumner Wilson in the press for a decade after that. I reached out to Salem research librarians, hoping to fill in the gaps, and got this response:

“According to the 1900 Federal Census, Charles was living at the Almshouse in Salem. The Almshouse was a building that served as a poor farm or hospital for the contagious and mentally ill.”

In 1901, the same police marshal was brought up on charges connected to an officer’s financial impropriety. It’s impossible to know if the marshal was crooked. It’s impossible to know if he institutionalized Wilson to keep him out of the way. Or if Wilson was actually mentally ill, or despairing or destitute.

On Jan. 17, 1904, Charles Sumner Wilson died at the Danvers Insane Asylum.

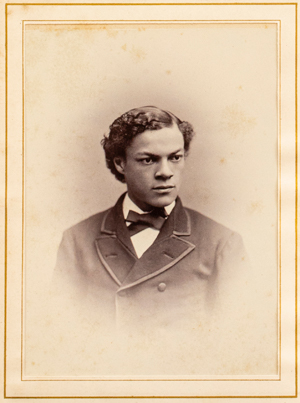

Charles Henry Moore, Class of 1878

The Black residents of Tarboro, N.C. crowded into a tobacco warehouse to hear the words of Charles Henry Moore. He talked for an hour. He had done many such talks, traveling 12,000 miles from town to town in his home state. On this day in 1917, he again made his case: State appropriations for Black schools are “pitifully small,” and let’s not count on local white folks for help. We must build new schools ourselves–and northern resources will support our resourcefulness.

This scene was described by Moore in an article titled “Rosenwald Schools of North Carolina.” Rosenwald Schools were a joint effort thought up by Booker T. Washington, leader of the Tuskegee Institute, and funded by Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears Roebuck. Some 5,000 Rosenwald Schools were built between 1915 and 1932, a third of the total of Black schools in the South. Moore was the Rosenwald agent for North Carolina.

Charles Henry Moore was born in Wilmington, N.C., in 1855; his mother was Black and his father was white. His high school years were split between Howard University’s college preparatory department and Smith Academy in Hatfield, Mass. We know almost nothing about his time at Amherst.

Moore’s influence on Black education in the South was prodigious. He was North Carolina’s first state schools inspector before he started working for the Rosenwald fund. His 1916 report on the state’s schools turned up extensive evidence of inequity, as white schools siphoned off funding meant to be split with Black schools. At times, Moore faced hostility on his visits and had to escape at night for his safety.

His efforts spanned wide: Moore was a founder of the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. Today, the university has a research lab named the in his honor. He became a teacher and principal in the Greensboro, N.C., school system and helped to organize the North Carolina Teachers’ Association. A local grade school was named for him.

His work also extended beyond the field of education. Moore was closely allied with Booker T. Washington and served as vice president of the National Negro Business League. And he is “credited with having begun the agitation” to fundraise for building a hospital to serve the Black population of Greensboro.

Born into slavery, he died in 1952, at age 97. It was two years before the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Wiley Lane, Class of 1879

Frederick Douglass spoke at his funeral.

Frederick Douglass spoke at his funeral.

He was one of many who stood up that day. Douglass had found “surprise and delight” hearing an art lecture from Wiley Lane, the first African American professor of Greek at Howard University. Lane had attended Douglass’s 20th anniversary commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation. Said Douglass: “He was a rising young man and an honor to humanity.”

Lane died at age 32, of pneumonia, in 1885. As Howard Professor Francis L. Cardozo eulogized: Lane wanted to occupy the position of Greek professor well “so that he might aid in removing the stigma on his race of their inability to fill such positions.”

Before he became a professor of Greek, he was assistant principal, then principal, of Howard’s Normal Department, training teachers to serve the Black community.

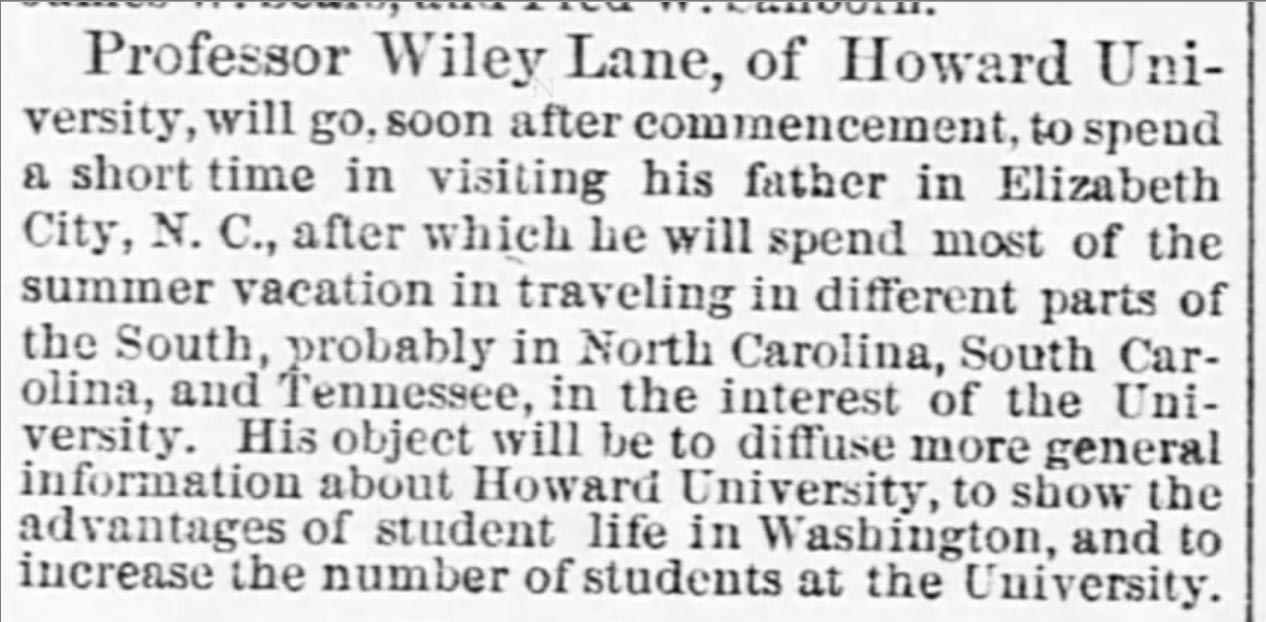

National Republican, Washington, District of Columbia, June 2, 1881. “Professor Wiley Lane, of Howard University, will go soon after commencement to spend a short time in visiting his father in Elizabeth City, N.C., after which he will spend most of the summer vacation in traveling in different parts of the South, probably in North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee, in the interest of the University. His object will be to diffuse more general information about Howard University, to show the advantages of student life in Washington, and to increase the number of students at the University.”

Wiley Lane was born in Elizabeth City, N.C., in 1852, the child of two free parents. After attending Howard’s college preparatory department, Lane headed to Amherst, drawn by its illustrious classics department.

Senator George Hoar (R-Mass.) also spoke at the funeral, and said that he had known Lane for 15 years and had gone to his Amherst commencement. At that time, Hoar met with President Julius Seelye, who remarked that Lane “was a universal favorite both with teachers and pupils.” He was Phi Beta Kappa at Amherst.

Lane took a robust role in the Black intellectual circles of Washington, D.C., in the 1880s. If there were celebrity professors at that time, he would qualify. He made many public appearances: In 1882, at a D.C. banquet for a Haitian diplomat, he offered a talk titled “The Man of Letters.” In 1883, he delivered an address on “The Freedman’s Bank.”

Since 2003, an exhibit called “15 Black Classicists” has traveled to numerous venues, including Howard. Wiley Lane is one of those 15.

Michele Ronnick, a professor at Wayne State University, created the exhibit. As she told The Guardian: these historical figures are “waiting patiently for us to find them. It is an intellectual heritage in which all Americans can take pride.”

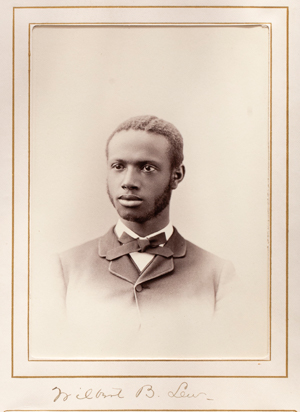

Wilbert Lew, Class of 1883

There were almost no official veterinary schools at the time. The profession was in its colt stage: young and wobbly. It wasn’t until 1945 that Tuskegee started the first program for Black veterinarians.

In census and directory records, Lew is listed as working at the J.N. Leonard silk factory in Florence, Mass., part of Northampton, in 1888-89. From 1890, he is listed as a veterinary surgeon and dentist in Florence.

Wilbert Blanchard Lew was born in Gardner, Mass., in 1861, and spent part of his childhood in Florence. He lived in the same Pine Street neighborhood where Sojourner Truth and David Ruggles had once dwelled, when the town was a hive of abolitionist activity. His father’s occupation is listed as “hair dresser,” his mother’s as “keeping house.”

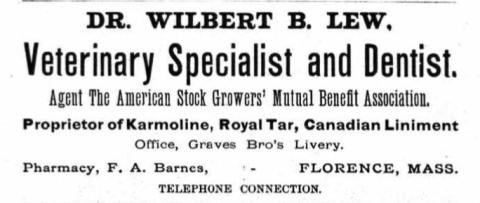

There was an ad for his services in the 1891 city directory: “Dr. Wilbert B. Lew, Veterinary Specialist and Dentist. Agent for The American Stock Growers’ Mutual Benefit Association. Proprietor of Karmoline, Royal Tar, Canadian Liniment.”

In 1920 he was appointed “inspector of animals” for the town of Amherst. He died in September 1923, after four decades of treating and educating horses and other animals, and riding into the dawn of a new profession.

Portraits courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.