Danielle Benedetto instructing students in a math class (photo by Rob Mattson)

A few years ago, I ran into Caroline MacGillivray ’19 in Valentine Dining Hall, and we started chatting about everything from country music, to the merits of the salad bar, to her recently declared math major. Which teacher has influenced you most so far? I asked, and her answer came back swiftly: Danielle Benedetto. “We all call her The Math Mom,” MacGillivray said, because Benedetto was over-the-top caring as well as rigorous.

As Benedetto, senior lecturer in mathematics, later told me of her relationship to her students: “I’ll walk you across a tightrope, but I’ll hold your hand while you’re doing it.”

A first-generation college graduate, Benedetto joined the department in 2009. And since then, the number of math majors has tripled at the College, and the number of first-gen and women math majors has gone up nearly fourfold. “About 80 percent of Amherst students are taking at least one math class,” said Benedetto. She finds this remarkable, “especially in a place with no math requirement.”

She has taught a range of 100-level calculus courses, almost exclusively to first-year students, and has become legendary for her support system, sending a steady stream of individual check-in emails to her hundred or so students each semester and offering a whopping 20 (!) office hours a week. She also teaches in the Summer Bridge program, and takes the lead in placing first-year students in the beginning math class that’s right for them. As she says: “I’m best suited to get my hands on these students who don’t think they belong in math or STEM classes.”

When I mentioned MacGillivray, Benedetto brightened. “Caroline was a student who never thought she would take math but had a good experience, then took another math course and another,” she said. “That’s a perfect story of someone who didn’t think they necessarily belonged. Everybody belongs in my classroom. And if you don’t have the same preparation, I’ll give it to you and show you how to succeed.”

This year, Benedetto was awarded the Jeffrey B. Ferguson Memorial Teaching Prize. Named for a beloved Black studies professor, the award celebrates the art of teaching and has been given since 2019. Previous recipients include Adam Sitze (law, jurisprudence and social thought); Marisa Parham (English); Rhonda Cobham-Sander (Black studies and English); and Sheila Jaswal (chemistry).

I caught up with Benedetto to learn more about her life, her work and her impact on the College.

Can you tell us a bit about your background?

I’m from a small town in Maine called Gardiner. My dad was a shipbuilder, a welder and more at Bath Iron Works, and my mom was a home typist who ran a small business out of our house. So we just didn’t talk about academics where I grew up. We did learn to work very hard, though. I feel like hard work fuels success, which ends up being a theme in my classroom. Somehow, I found my way to Colby College, where I got full financial aid.

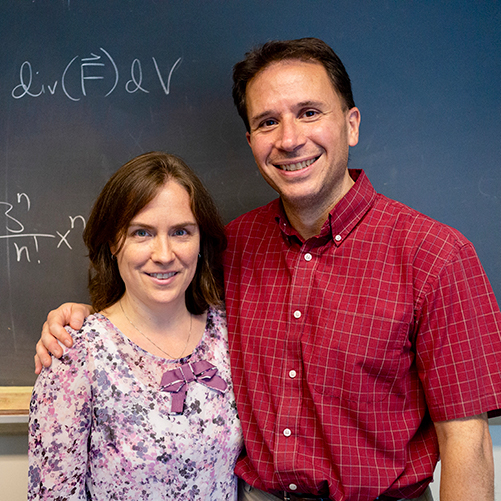

Danielle Benedetto with her husband Robert Benedetto, Wiliam J. Walker Professor in mathematics and astronomy (photo by Michael Reid)

I never even dreamed that I would go to college, and then I found some professors who completely changed my life. They took me under their wing, taught me everything you need to know about college. I didn’t even know what “having a major” meant. I thought you went to office hours only if you did something wrong. Then one day, one of those math professors—Fernando Q. Gouvêa—told me that I should go to graduate school. It’s probably one of the best days of my life, because he didn’t laugh at me when I said “What’s that?” I ended up getting my Ph.D. at Brown, which is where I met my husband (Rob Benedetto, the William J. Walker Professor in Mathematics and Astronomy). He gave me a tour of the department on my first day.

Were you always drawn to math or to being a teacher?

From kindergarten to high school, I can remember helping the students around me. Teaching just feels like putting on the right skin. As a teacher, I would describe myself as organized and passionate. But I didn’t even know you could be a math major. Based on what I saw on TV, you could be an “-ist,” like a chemist or a biologist. At Colby, I started as a chemistry major, but I was sitting in a physical chem class one day, and there were all these math formulas floating around, and it just hit me that it’s the math that I’ve loved in the science this whole time. Luckily, I had been taking math classes, too, and that’s something I’ve transferred over to my current students: keep on different pathways, rather than worry about exactly what you’re doing.

What do you love about math?

I enjoy the puzzling aspect of it. Even more, I enjoy putting the argument together to convince somebody that it’s correct. That is something you can take to any field. Many of my students say, “I was never good at math in high school.” I think if you take the focus off of the raw mathematical content and you teach them how to learn mathematics, then that completely changes their experience. Calculus is the study of changing quantities, and so they learn quantitative reasoning, how to support their argument. If I could call Math 121 “Making Good Arguments,” I would.

How does your experience as a first-generation college student help you connect with your first-gen students?

The first thing I do is share my own story in class. And often you’ll see the first-gen students in the room snapping, because they immediately feel seen, like they can have someone they can trust. My colleagues are just as good at this as I am, even if they’re not first-gen, and we have this great community in the math department. The key word for me with students is “preparation.” It’s not talent or any other measure. The most important thing is to get them over that hurdle of being afraid of asking for help. Everybody at Amherst needs help at some point. Entering college is sort of like dodgeball. All of a sudden, these complex situations get chucked at you, and you might get hit the first couple of times, but I want to teach them to catch that ball.

I have to say I was kind of blown away by the number of office hours that you offer. The average here is about six per week. You do 20 or more.

It’s a little crazy, but first-gen students work a lot, right? If you’re on financial aid, you have a job. I worked 30 hours a week at Colby. So I want to be as accessible as possible. Office hours are for everybody. It’s an open study group, and friendships are built as they stumble through the challenges together. And then they realize: Oh, that was so much easier than slogging through it on my own, late at night. And they’ll come back again. I work my way around the group and make it fun. I try to bring joy, here and in the classroom. Also, I have candy. Everybody loves the Kit Kats. And I do private sessions for shy students who don’t like the group setting. There are students who truly hide out, but I just don’t let them go.

You are the person who assesses math-class placement for incoming students. How does that work?

I spend many, many hours skimming through records to keep the overprepared students out of the lower level. You don’t want the better-prepared people muscle-flexing in class, making the less-prepared feel like it’s not a safe place and they can’t ask questions. I probably do about 3,000 emails between July and August back and forth with the incoming class. This past year was even trickier, because high schoolers didn’t take the AP calculus test. So it’s really sort of a personal measure of getting this formula just right, and we really rely on the people in Admission, plus Jesse Barba in Institutional Research and Registrar Services. And I share this work with [Lecturer] Stephen Cartier in chemistry. In the most recent years, we’ve got our placement formulas so accurate that no student has had to move up or down in the first few weeks of either chemistry or calculus.

This may be getting in the weeds of academia, but I want to ask about your title. “Senior lecturer” is a position in which you teach, solely, and don’t do research. And it’s not on a tenure track. How do you feel about the direction your career has taken?

Good question. In graduate school, I did fine with my research, but I didn’t love it. And I was definitely behind. I went from being valedictorian of my college class to really struggling in graduate school. Because I came late to the math major, I know what it feels like to have less preparation. Everybody I was with had had graduate classes as an undergraduate. Also, there was a problem with my thesis: I was trying to build it off a published paper that turned out to be wrong. Plus, I wanted to be a stay-at-home mom. I actively stayed at home with our three kids for nine years until Rob got a job at Amherst and our youngest child went to kindergarten. Greg Call, dean [of the faculty] at the time, knew about my teaching from graduate school, and he created a lecturer position for me.

What do you think of being called “The Math Mom”?

I love it. I treat my students like my children. I want them to know that they’re cared for. I mean, what’s special about Amherst is you’re coming here for a great education, but it’s a small liberal arts school. You should have people care for you inside and outside the classroom. We live right across the street from campus. Our kids grew up eating in the dining hall. We’re always around, we’re always at the athletic events, music events. I think it’s really important that students see you around. And I think if they see you around, they feel even safer asking questions in class.

How do you feel about getting the Ferguson teaching prize?

I’m overwhelmed with gratitude. I was shaking the night when I heard I’d won. I’m not a tenure-track faculty member here, and I don’t teach students at the upper level. I never thought a lecturer would win that award. I’m thankful that people recognize how hard I work, because I really am working very, very hard. Faculty at Colby College truly changed my life. They believed in me. My whole teaching career has been about paying this forward. Every morning when I walk up the hill to work, I think about how lucky I am—and what I can do to change someone’s life that day.