Building Community with Students to Investigate Issues of Diversity and Inclusion in STEM

Featured Staff and Faculty:

Image

Megan Lyster

Image

Leah Schmalzbauer

Image

Sheila Jaswal

We co-taught the Being Human in STEM (HSTEM) course in Spring 2020. Enrolling 17 students majoring in STEM (Biology, Biochemistry & Biophysics, Chemistry, Computer Science, Physics/Astronomy, Psychology, Neuroscience, and Math and Statistics) and non-STEM (Sociology, American Studies, Black Studies) fields, this interactive course combines academic inquiry and community engagement to critically investigate diversity and equity within STEM fields, in the context of Amherst and beyond. In the first half of the semester, we read interdisciplinary literature on the ways in which identity - gender, class, race, sexuality - and geographic context shape STEM persistence and experiences of belonging. In the second half of the semester, students designed group projects to apply their research, develop resources, and engage the STEM community.

From the very beginning of this course, the focus was on building trust and community among students and between students and instructors. This course involves engaging with complex topics around inequity and identity, and asks students to bring their lived experience into dialogue with challenging academic literature focused on social inequality. A strong sense of community is critical to meeting the learning goals of this course.

There are a number of practices that we enacted early in the semester to build this community, many of which built on the Restorative Justice practices (see Karp, 2019) that two of the co-facilitators had engaged with during the 2020 interterm session:

- Physically structuring the course so that we all sat in a circle each class session. The goal was to create an equal power-based positionality for each member of the class. Fortuitously, when the class shifted to remote meetings in the middle of the semester, Zoom meeting spaces create a similar dynamic in which each face is an equally-weighted presence.

- Prompting students and co-facilitators to share personal aspects of oneself, starting with how they would like to be addressed and why. This activity led to students discussing the origin of their names and faculty describing their preferred manner of address (e.g., “Dr. J,” “Professor Schmalzbauer and/or Leah,” “Megan”), and why.

- Including one-word “check-ins” in which everyone shared a one-word descriptor of how they were feeling or what they were thinking at the start of most class sessions. This practice provided a warm-up that met all class participants where they were, acknowledged the need to transition to the work of the class, and involved all class participants equally.

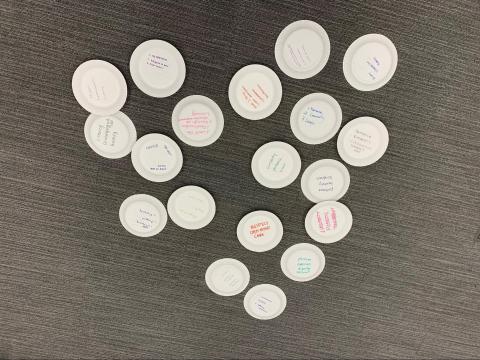

- Establishing group-developed community norms. After the add/drop period, we engaged in a joint conversation about the behaviors and ways of interacting that we felt contributed to a productive learning environment. Again drawing on the restorative justice model, every class participant (instructors and students) wrote on a paper plate (pictured below):

- Three qualities or values you want to ask of our group in our work together as a class

- Three qualities or values you will offer to the group

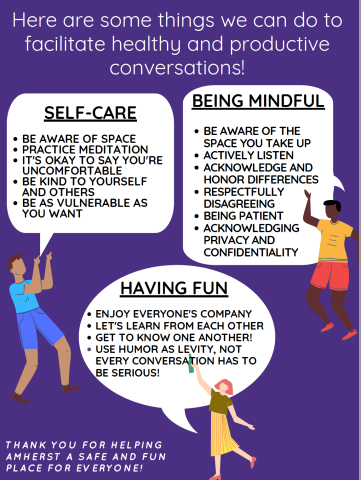

Once everyone had completed their individual reflections on the paper plates, each person shared what they had written and then Megan engaged the class in an in-depth conversion about the class norms that we wanted to establish in order to support kinds of contributions that individuals had identified. To capture these emergent class norms, one student then developed a digital poster of our shared class principles, which is attached in an accessible format below.

Following the shift to remote teaching and learning, there were several practices that we employed to maintain community, all of which established class rituals. We found that these rituals provided a source of energy, comfort, and community for all of us. For instance, early on in the semester, Sheila had taken inspiration from our community norms discussion to play relaxing music as students filtered into class in the morning. She continued to play the same music at the start of each synchronous Zoom session, which helped to invoke our shared experiences in the classroom. We had regularly documented our work together through photographs while we together, so we adopted the practice of taking a whole-class screenshot during each class meeting and added the image to our running GoogleDoc class meeting notes. Finally, at the end of each class meeting, we invited students to stay on the Zoom call for informal conversations. As students had already warmed up with each other throughout the class session, these 10-20 minute conversations were a point of fun and sharing. For instance, one conversation involved class members and instructors sharing baby pictures with each other! We found that inequities in students’ home learning environments were on display during remote class video meetings, and reinforcing class rituals provided a sense of continuity in our class, which led to a sense of comfort during a challenging end to the semester.

In end-of-course evaluations, students wrote that they appreciated that we “acknowledge students' humanities by presenting your own unabashedly, and I will never be able to thank you enough for it.” Another student wrote that they thought of us as a “compassionate and deeply thoughtful friend” who “cares not only about what you think about the class but also how you're doing as a general human being.” Finally, a third student said that “X is so understanding and seems genuinely interested in the lives of her students and hearing what we are up to. Y is as well, and I feel especially comfortable with her because I feel like we have so many shared experiences through STEM. The two of them together are such an amazing teaching team. They bring really different things to the table but work very well together.”

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Being Human in STEM syllabus | 96.81 KB |

| Class norms poster | 70.41 KB |

| HSTEM Community Norms poster in Accessible Format | 72.93 KB |