The Great First Folio Caper

By Roger M. Williams '56

|

If you’re a thief in search of a big payoff, stealing a Shakespeare First Folio is probably the dumbest move you can make. A couple of hundred First Folios—the first collected editions of the Bard’s plays—still exist, and thanks to incredibly painstaking scholarship as well as quirks in 17th-century publishing, experts can readily identify them. That tends to reduce the potential sales market to zero.

Nonetheless, in December 1998, somebody lifted the so-called Durham First Folio from a university library in that northeastern England city. The book’s estimated value was some £3 million, the university said—that is, if anyone would pay it.

Flash forward to June 2008. A man named Raymond Scott walked into the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Amherst-affiliated institution in Washington, D.C. Scott carried a book that looked very much like a First Folio—more specifically, like the Durham First Folio—and he was seeking an evaluation and appraisal of it. Would a sane person do that? Is Scott the Thief of Durham? Therein hangs the tale, one festooned with Gucci loafers, a Ferrari 456 and a young female consort who became known as “The Cuban Cutie.”

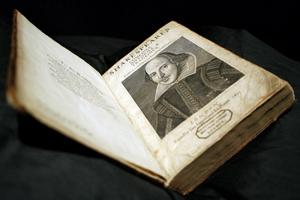

Taken collectively, First Folios have been called “incomparably the most important work in the English language.” Only half of William Shakespeare’s plays were published before his death in 1616, in volumes known as quartos because of their smaller size; they omitted such monumental works as Macbeth, Julius Caesar and As You Like It. The First Folio, entitled Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories & Tragedies, appeared seven years after his death. The collection had been assembled by two fellow actors and was published by a group of booksellers/publishers (then known as “stationers”). According to the reigning expert on the subject, Peter W. M. Blayney, about 750 copies were printed. They apparently sold out, leading to publication of a Second Folio in 1632. Two more editions appeared before the end of the 17th century. Nowadays, First Folios are far more valuable than any of their successors.

Oddly, given the importance attached to it, the First Folio is “not a particularly rare book,” Blayney writes in The First Folio of Shakespeare. The Folger owns numerous rarer ones, including the world’s only 1594 quarto edition of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus.

Roughly 230 First Folios have been catalogued, thanks principally to the industriousness of one Anthony James West, who has traveled the world compiling a “census.” Of that total, the Folger has 82, by far the largest single collection and a tribute to the library’s acquisitional energies and power. (Meisei University in Japan has the next largest number, 12, and the British Library a mere eight.) Notes Steven K. Galbraith, the Folger’s curator of books, about Henry Clay Folger, Class of 1879, who founded the library—now administered under the auspices of Amherst—with his wife, Emily, “Mr. Folger had a thing about First Folios. At the time he was buying, the British were cash-poor and land-rich.”

The First Folios were published in a manner that would today be inconceivable. Spellings varied widely; misprints abounded, and in at least one instance, an entire line was omitted; different typefaces appeared in a single play; trimming of edges followed no pattern, resulting, in some cases, in parts of the text being cut away. In addition, and hardly a surprise after almost 400 years, the folios everywhere are now in various stages of disrepair; some amount only to fragments. (No copy is known to have survived in its original binding.) They’d be far worse, perhaps in tatters, except for the fact that the printing was done on rag paper, which is acid-free and durable.

Thefts of First Folios have periodically occurred over the centuries. Of one particular Shakespeare scholar in 19th-century England, it was said, “If he walks into your library, be careful when he walks out.” Pre-Durham, the most recent theft took place in 1940 at—wouldn’t you know it?—the Chapin Library at Williams College. After discovering that the book was too hot to be sold, the thief, who’d forged papers to identify himself as “Professor Sinclair E. Gillingham” of Middlebury College, turned himself in and fingered a trio of fellow conspirators. The trial judge received a letter asking for leniency for one member of the group because he was an aircraft worker “designing a special military plane.” The letter turned out to be a forgery. (Mark Rondeau’s witty account of the entire event, complete with lines from Shakespeare’s plays, is at www.markrondeau.com/folio.html.)

So the disappearance of the First Folio from the library at Durham University was far from unprecedented. Neither was it very surprising—at least not to those familiar with security in similar English institutions. According to Detective Constable Tim Lerner of the Durham Constabulary (the city’s police department), who worked extensively on the case, the volume, and a half-dozen other antique books and manuscripts that disappeared with it, were kept in a glass cabinet equipped with only “flimsy” locks. Thus, the detective says, it was simple for the thief or thieves “to pry the cabinet open with a screwdriver or something similar. There wasn’t any security, in the way of staff, cameras or whatever.”

In fact, Lerner adds, “It was several days before the items were discovered to be missing. That happened when a visitor looked into the cabinet and saw it was empty.” Back in the late 1990s, he says, security that lax was practiced at libraries across England, including the monumental British Library in London. “They believed that the only people who’d enter were there to see the exhibits. All that’s changed now.”

When tall, slender Raymond Scott showed up at the Folger Library, 10 years later, he was toting a briefcase and in it a plastic bag. Standing before Frederick Baylor, a veteran guard at the Folger, he took out a book. Or rather, a sort of book: the binding was missing, leaving the first few pages loose; also missing were both the title and final pages. Baylor recalls, “He had on a colorful T-shirt, jewelry and sunglasses.” (Fendi sunglassses, to be exact.) “He really stood out.” At the Folger, however, his English accent was unremarkable.

Scott told Baylor he had a book he thought was valuable and wanted it examined. He was ushered into the office of Richard Kuhta, the Folger’s Eric J. Weinmann Librarian. There, Kuhta later told Folger Magazine, Scott declared that “he’d just arrived from Cuba,” where a friend had given him this book. The friend had “inherited” it, said Scott, who then pressed Kuhta about whether it might be important and valuable. The librarian, already wary, said the Folger staff could evaluate the volume, and Scott agreed to leave it for that purpose. The Folger’s head of reference, Georgianna Ziegler, promptly took it into the vault and set it alongside copies of all four Folios. From that she concluded that Scott possessed a First Folio. Its provenance remained uncertain.

Two days later, Scott, by then installed in a suite at Washington’s expensive Mayflower Hotel, returned to the Folger and got the good news. But not the book: Kuhta, buying time, told him that Ziegler’s “preliminary” assessment needed confirmation. Instead of sensing imminent danger, Scott chattered about his prized possession to The Washington Post. Soon he was back at the library, bestowing on Kuhta gifts of Cuban cigars, a box of expensive bow ties and 25 $100 bills. The cash, he announced, was “for membership in the Renaissance Circle,” a group of high-level Folger supporters. On his final visit, the following day, Scott brought a cake for afternoon tea; Shakespeare’s name was written on top of the cake—and misspelled.

By this time, the book had been placed in the hands of Stephen C. Massey, an eminent rare-book appraiser based in New York City. Scott knew that, but he didn’t seem panicked. Instead, Folger officials speculate, he may have seen it as a great opportunity. Says conservator Renate Mesmer, “Stephen Massey is a big-time book seller, too, and Scott might’ve seen him as a guy who could find a buyer” who would snap up the merchandise and make Scott rich. The prospect of getting arrested seemed not to occur to him. With at least a metaphorical wave of the hand, he announced he was returning to Cuba, leaving his treasure—as well as his future—in the Folger’s hands.

In what he describes as “a nanosecond,” Massey confirmed that Scott’s book was the Durham First Folio. Among the telltale clues: the dimensions, 330 by 210 millimeters (true of only two of the surviving volumes); gilt-edged pages; and a manuscript inscription, “Troilus and Cressida,” added to the table of contents.

Although Folger officials found Massey’s assessment conclusive, they pressed for additional confirming details. Says Galbraith, “We were fine with the dimensions and other similarities Massey noted. But how would a jury react to those?” The curator’s cautionary approach led to still another persuasive comparison—of what experts termed the “typographical variants” seen in Scott’s book and known to have been in the one stolen from Durham.

Based on Massey’s assessment alone, however, it was time to switch from scholarship to law enforcement. So Kuhta—after notifying Paul Ruxin ’65, chairman of the Folger’s Board of Governors—contacted the Washington, D.C., field office of the FBI and the head librarian at Durham University. Other calls went to the British Embassy and Scotland Yard. The latter brought in the Durham Constabulary, which would do the heavy lifting in the case.

Although the theft had triggered what some overheated media called at the time “a worldwide manhunt,” the hunt at first galloped right past the town where Raymond Scott lived—about 10 miles from the Durham University library. The town bears the picturesque name of Washington, Tyne and Wear. By 2008, Scott, then 51 and a bachelor, had been living there for decades in his mother’s house. Armed with Massey’s and the Folger’s deductions, and prodded by crime busters on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, the hunters swerved and headed for Mum’s place. The Durham police seized more than 1,000 printed volumes that they turned over to specialists on old and rare books. The cops also questioned Scott at length, though they did not at that point arrest him.

The book raid caught the attention of not only the local newspapers but also the sensation-seeking London tabloids and—again—The Washington Post, which dispatched two reporters to Washington, Tyne and Wear. They all discovered an unimaginable feast. Scott, it quickly became clear, was as flamboyant as he was effusive. Neighbors on the sleepy cul-de-sac of Widgeon Close related stories of his succession of flashy sports cars: a Lamborghini, a Rolls-Royce, an Aston Martin and the latest in the line, the Ferrari. Some claimed, according to London’s Daily Mail, that “he often emerges in a silk dressing gown and sunglasses to iron the seats” of the Ferrari.

Scott greeted the media attention with exuberant relish. He was photographed flashing a broad smile while smoking a Cuban cigar and drinking Dom Pérignon from, as the Post put it, “the jeweled (Swarovski crystals) champagne flute he carries with him in his briefcase.” The Daily Mail, dubbing the affair “Shakespeare in lust,” reported an “assortment of expensive jewelry ... including a Cartier watch, Rolex bracelet, Versace ring….” Scott himself spoke about his pricey suits and periodic holiday trips to Paris and Monaco as well as Cuba.

All of that was remarkable considering the man’s apparent financial resources. “He has never worked a day in his life,” Detective Lerner says. “He’s lived on state benefits [a ‘carer’s allowance’ and a stipend for ‘incapacity’] and, in recent years, debt piled up on credit cards fraudulently obtained.” Thus he had an urgent motive for stealing, or at least helping to sell or fence, the Durham First Folio, the detective says: “to get out of debt and avoid the credit card companies foreclosing on him.” Further, Lerner observes, Scott “has a history as a thief. He stole books from shops”—including some of those found in the raid on his mother’s house.

Thievery wasn’t his only transgression of the law. Over the previous three decades, he had been convicted by courts 17 times for a total of 26 offenses, according to Lerner. They ranged from shoplifting to threats to kill to possession of an imitation firearm. Some involved the use of such colorful aliases as Andreas Benatar, Andrens Bewatar and Andrens Scott.

Scott portrayed himself as an aw-shucks sort of bibliophile. He told the Post he began collecting books only seven years earlier and said that at the time the Durham volume disappeared, “I wouldn’t have known the difference between a First Folio Shakespeare and a paperback Jackie Collins.”

Scott’s Cuban connection proved to be both colorful and tangled. The color lay mainly with 21-year-old Heidy Rios, a Havana chorus-line dancer whom the tabloids dubbed the Cuban Cutie and “Cuban Firecracker.” By Scott’s account, as reported in various news articles, he fell for her while watching her perform at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba in 2007. Romance followed, as did two more trips to Cuba. Rios eventually introduced him to self-professed bibliophile and former Castro bodyguard Odeiny “Danny” Perez, who, Scott told reporters and police, had the tattered book the two men wound up hoping was a First Folio. Since travel restrictions prevented Perez from bringing it to the United States, his new business partner agreed to do it—for a healthy share of whatever profit resulted.

In June 2008, Scott proposed to the Cutie on bended knee, and she accepted. The June date is significant, because just after that, he later said, he flew from Havana to Washington with the book. He claimed it was defaced when Perez gave it to him. Those two assertions, says Lerner, are part of Scott’s “pack of lies. We know that Scott went to Washington directly from Heathrow, not from Cuba. And if he got the book with those important pages plus the binding missing, how could he believe it was a First Folio? He’s no expert.” Lerner’s conclusion: Scott himself did the defacing, to prevent its being identified as the hot item from Durham. Soon after he returned from Washington, Durham police arrested him. A court released him on bail.

Two years later, Massey says, he received a phone call from none other than Raymond Scott, who, awaiting trial, was still trying to convince the world of his innocence. “I was on the phone with him for 45 minutes,” Massey recalls. What could a rare-book appraiser and a petty criminal find to talk about for that length of time? “He did most of the talking,” Massey replies dismissively. “He was drunk.”

In midsummer 2010, at the Newcastle Crown Court, Scott went on trial for theft, handling stolen property and removing it from the country. On opening day, he arrived in a silver limousine, telling anyone who’d listen that the book he brought to the Folger was not the Durham First Folio. As reported by a British journalist in Folger Magazine, Scott cut a predictably odd figure in court: “1950s checked hunting jacket, with leather elbow patches, buttoned breast pockets and pleated back … tinted lenses [in] heavy glasses with gold ornamental sides … oversized, glittery belt buckle .… fake-tan face ... spent much of his time in court stroking his hair into place.”

The trial lasted three and a half weeks, and the defendant did not take the stand. Proving that he had handled stolen goods was hardly difficult; proving that he’d removed the First Folio from the home country, hardly more so. But in trying to make the theft charge stick, Lerner says, the prosecution suffered a pair of setbacks. “We wrote to the Cuban authorities for permission to conduct an in-person interview with the guy Scott said gave him the Folio. We got the okay—but not in time to do the interview before the trial.”

In addition, a prolific convicted book thief named William Jacques, whose testimony might have convicted Scott for the Durham theft, refused to provide it. “During the investigation,” Lerner says, “Stephen Massey mentioned Jacques and said he, too, may have had a connection with Cuba. Indeed, I discovered that Jacques, while out on bail in 1999, had fled there. Disclosure rules in the U.K. [as in the U.S.] required that the prosecution inform Scott’s lawyer of this revelation, which provided him with a defense to the theft charge when he seemed not to have one. He could now contend—and did—that Jacques stole the Folio and took it to Cuba, and that nine years later, it was given to the innocent Scott.

“When I visited Jacques in prison, he told me told me he had no involvement in the Folio theft, no knowledge of Scott and no connection with Durham,” Lerner says. “I asked him to give this evidence at the Scott trial, but he refused unless he was released from prison.” That, says the detective drily, “was not an option.”

Testimony at the trial included a number of choice Scotticisms. According to Durham Detective Inspector Mick Callan, Scott told police officers, “I’m an alcoholic and need two bottles of top-of-the-range champagne every day, but only after 6 p.m. I hope you have some in the station…. I don’t have to answer your futile questions.”

Scott’s attorney, Toby Hedworth, portrayed his client in distinctly unflattering terms. “He’s feckless and a spendthrift,” Hedworth declared in his closing statement. “He is, you may think, of questionable taste. Yes, he’s had his head turned—he fell into a honey trap….

“But is this naïve mummy’s boy simply out of his depth? He’s someone who genuinely believes a 21-year-old dancer is his fiancée. Ladies and gentlemen, there’s no fool like an old fool. May it be that he’s been had over [duped]? No doubt loving every minute of it. But if that may be the case … your verdicts in respect to these charges would be ‘not guilty.’”

Even his attorney’s disparaging words could not spare Scott conviction on the two lesser charges of handling stolen goods and removing them from the U.K. But the lack of hard evidence that he personally “nicked” the Folio, combined with William Jacques’ refusal to testify, made a guilty verdict on the much more serious charge of stealing the Durham Folio all but impossible to sustain. After the jury delivered its findings, Judge Richard Lowden called the defendant, to his face, a “fantasist” who “wanted to fund an extremely ludicrous playboy lifestyle in order to impress a woman.”

|

The judge termed Scott’s crimes “cultural vandalization” that ended with the disappearance and desecration of “a quintessentially English treasure.” The sentence: eight years in Her Majesty’s Prison Castington.

Scott soon made plans to write a book about his escapades with the Durham First Folio. Throughout the United States, so-called Son of Sam laws prevent convicted criminals from profiting in such a manner from their crimes, and the U.K. has similar, but vaguer, statutes. Nonetheless, a small London publishing house says it will bring out Shakespeare & Love this spring. The cover pictures Scott dressed in a ruffled-neck shirt, holding a champagne flute and an outsized cigar.

For the Folger, Scott’s conviction ended a long period of unusual publicity and media attention. Librarian Kuhta, who testified for four hours at the trial, became so thoroughly sick of the matter that, after retiring in 2008, he declined to be interviewed about it. At least for this article, however, others at the library seemed to relish the opportunity to recount details of Scott’s actions and the library’s role in identifying the stolen First Folio and trying to help catch the thief. Henry Clay Folger was unavailable for comment.

Roger Williams has been a magazine journalist since graduating from Amherst. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Planning to be in Washington, D.C., this summer? The Folger Shakespeare Library will hold a major exhibition on the First Folio, including the Durham First Folio. The exhibition, titled Fame, Fortune and Theft: The Shakespeare First Folio, will be in the library’s Great Hall from June 3 to Sept. 3. Tickets are free. Go to www.folger.edu/shakespearefirstfolio for details.