By Rand Richards Cooper

Think of a moment when you saw someone you loved for the last time. Perhaps he or she was old or gravely ill. Knowing this might be a final encounter, you found a way to say goodbye. Days later, a funeral followed.

We want our final partings to work this way, letting us see loss as it approaches, giving us ritual to tame the unruliness of grief. But all too often, the gods have other plans. Especially in wartime.

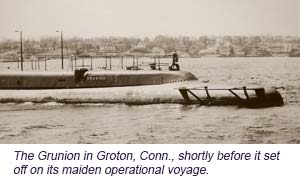

The last time John Abele ’59 saw his father was a Sunday in May 1942, at the submarine base in Groton, Conn., where Mannert L. Abele was stationed. With his parents and older brothers, John, then just 5 years old, ate lunch at the Officers’ Club. Afterward their father sent them home to nearby Mystic, saying he had things to do. In fact, Lt. Cmdr. Abele wasn’t going on some errand, but on a mission that Navy policy forbade him from revealing even to his family. Hours later, the USS Grunion, a 311-foot, diesel-powered Gato-class submarine, proceeded into Long Island Sound, headed for war duty in the North Pacific—its crew of 69 men commanded by the 38-year-old Annapolis graduate known to his family as “Jim.”

They never saw him again. Four months later, the Abele family received a terse telegram from the Navy, informing them that, “following action in the performance of his duty,” Jim was missing. Fifty-two American subs went down during World War II, and the Grunion was one of a handful about which next to nothing was known. Years passed, then decades, and the sub’s official designation remained “overdue, presumed lost.” End of story—or, rather, no end of story.

Except that, once again, the gods had other plans. Six decades later, in a fantastic concatenation of events, John Abele—by now a billionaire inventor and businessman—brought together the power of the Internet, the efforts of a far-flung network of helpers and a lavish measure of luck to add a final chapter to this story, one that would clear up the Grunion mystery and let the families of its long-vanished crew at last close the book on their loved ones’ fate.

Retired from Boston Scientific, the medical instruments company he co-founded in 1979, Abele today sits on various boards, runs his own conference center and chairs his family’s foundation, Argosy, which in 2006 gave the money to create Amherst’s Center for Community Engagement. Abele flies around in his personal Citation X jet. He’s friendly with men like Dean Kamen and Craig Venter, fabulously successful inventor-entrepreneurs who share his passionate interest in technological innovation and the promise it holds for the future.

That Abele would become one of America’s wealthiest people would have seemed unlikely in the aftermath of World War II, when his family faced life with scant resources and no man on hand. Catherine Eaton Abele, known as Kay, got a job as a music teacher, scraped together $3,000 to buy a house in Newton, Mass., and went about teaching her three sons self-reliance and a certain emotional stoicism. When a death benefit arrived from the government, Kay sent the check back. Their father was missing, she told the boys, not dead. And other families needed the money more.

The Abele and Eaton families were “classic Yankee types,” John Abele recalls. Self-pity was not on the program. At 7, John was stricken with osteomyelitis, a bacterial infection of the bone marrow, and endured multiple surgeries and years of having to use crutches. He got so good with them that he could outrun other neighborhood kids; he turned a drawback into a competitive advantage. Ditto for growing up without a father. “It gave us an ‘I think I can solve that problem’ attitude,” he says today.

I met Abele at his house in Shelburne, Vt., where his hillside farm serves up big views of Lake Champlain—the scene, fittingly, of a crucial Revolutionary War naval battle, won by a motley American fleet under Benedict Arnold. “Right down there,” Abele said, pointing out his living-room window to the battle site. “Arnold was a terrific general. Good to have on our side. For a while, anyway.”

A trace of a limp testifies to Abele’s childhood illness, but he is notably agile intellectually; get onto one of his pet topics, like higher education or the latest Malcolm Gladwell book, and he speaks in a rush of enthusiasm, the ideas tumbling forth. The youngest of the three Abele boys, he remembers the least about his dad: “Just fleeting little elements, like him giving me money for brushing my teeth.” With his older brothers, Bruce and Brad, Abele enjoyed a classic boy’s life in the postwar era. “We did more with less,” he says. “We invented things.” Family photos show a homemade trampoline, a homemade surfboard and other jerrybuilt devices. The boys whose father was lost at sea seemed particularly drawn to aquatic inventions. The homemade aqualung. The pneumatic speargun. The underwater vehicle fashioned from a bike, its rear wheel replaced with the fan blade of a car cooling system as a pedal-driven propeller. Bruce still laughs about the “Jesus shoes” John made while at Amherst, designed to facilitate walking on water.

After Amherst, where he double-majored in physics and philosophy, Abele went to work, first for a light-fixture company in the Midwest, then for a small medical company near Boston. Soon he branched out on his own. His experience as a self-taught inventor, his innate ease with people and the broad reach of a liberal arts education equipped him to conceive a company that would develop innovative medical technologies, such as the balloon catheter and the stent, while radically revamping the way such companies did business with the medical profession. By the 1980s, Abele, a man without a graduate degree, was teaching courses to medical students and helping run Boston Scientific, a company whose revenues would grow to the many billions.

Meanwhile, the mystery of the Grunion remained, always there in the background of the brothers’ lives. Eventually, Brad Abele put together an unpublished manuscript, titled Jim, an account of their father’s life and what little was known about the loss of his boat. The book stoked the brothers’ interest in solving the mystery of the Grunion. But how? “From the last transmissions the Navy had received, we knew our dad’s ship was somewhere way up in the North Pacific,” Abele recalls. “But where do you start?”

The mystery seemed unsolvable. And it probably would have stayed that way, had not an Air Force officer named Richard Lane walked into an antiques shop in Denver one day in 1998 and purchased, for $1, a wiring diagram for the deck winch of a World War II-era Japanese freighter.

What happened next is a tale John Abele never tires of telling: “a fabulous story” that reveals the transformative power of the Internet, linking far-flung individuals to pool what he calls “the wisdom of crowds.” The phrase derives from business writer James Surowiecki’s bestselling 2004 book, which argued that aggregating the knowledge, perspectives and abilities of large groups can yield better problem-solving insights than any single member of the group—or, indeed, outside experts—might produce. The “wise crowd” metaphor dovetails with another of Abele’s guiding concepts, Metcalfe’s Law, which predicts that the power of a network will increase exponentially as the number of people in the network rises. Abele thrills at how today’s communication technologies foster “crowdsourcing,” mustering informal groups of people to solve problems. “You have to be awed by it,” he enthuses.

What eventually became the Grunion collective started, entirely accidentally, with Lane. After buying the wiring diagram that day in Denver, Lane promptly forgot about it. Rediscovering it in 2001, and curious now about its provenance, he displayed the diagram on a World War II naval history Web site. Soon afterward, a Japanese military historian named Yutaka Iwasaki posted a message identifying the freighter as the Kano Maru, a supply ship for Japanese forces in the Aleutian Islands. Iwasaki’s post included his notes on an article, written in 1963 by the captain of the Kano Maru, that recalled sinking a U.S. submarine in the western Aleutians.

A year later, in 2002, an acquaintance of Bruce Abele—his son’s girlfriend’s boss, a World War II history buff who had read Brad Abele’s Jim manuscript—forwarded to the Abeles a number of links to sites mentioning the Grunion. One contained Iwasaki’s post. Intrigued by the reference to an American sub sunk in the vicinity of their father’s last known location, the Abeles undertook a massive Web search, surfing hundreds of sites, until John found an e-mail address for a Yutaka Iwasaki. “I sent an e-mail, explaining that I was a son of the Grunion commander and asking if he was the same Yutaka who translated this article.” Within minutes, Abele received an extraordinary response: “I am he. I pray for the repose of your father’s soul.”

Iwasaki sent the original article, with his notes. It described a dramatic battle off the island of Kiska, one of two Alaskan islands occupied by the Japanese during the war. At 5:47 a.m. on July 31, 1942, the Kano Maru was torpedoed by the Grunion. The hit disabled the Kano Maru’s engine; as the freighter floated in the water, a sitting duck, the Grunion fired four more torpedoes—two that missed and two that hit but failed to detonate. The sub then surfaced, whereupon, as Iwasaki’s translation reads, “Kano Maru’s forecastle gun fired; fourth shot hit the conning tower of the sub. It is thought the last of Grunion.”

The last of Grunion: the Abeles had finally unlocked the fate of their father and his 69 men. But what to do now?

Another chance encounter changed the course of events. In January 2005, John Abele attended a conference in Florida where the guest speaker was oceanographer Robert Ballard, famed for discovering the wreck of the Titanic. Abele was captivated by Ballard and by the technical challenges of finding a submerged wreck. It would be a long shot, but Abele, a man who loves “entrepreneurial underdog stories,” couldn’t resist. “I went home and I suddenly thought, You know what? I can do this!”

Ballard put the Abele brothers in touch with a Seattle-based underwater surveying company that specialized in side-scan sonar, a device lowered off a boat and towed above the ocean floor. A friend of Bruce Abele’s son worked on a fishing boat in Alaska and sang the praises of his captain, a veteran fisherman named Kale Garcia. Garcia owned a 165-foot crab boat, the Aquila, and had experience in the remote Aleutian waters where the Grunion might be found. The Abeles hired him.

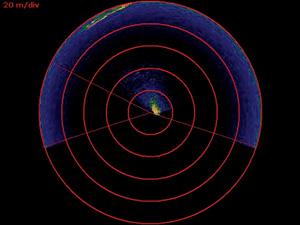

Sonar picked up an image on the ocean floor.

|

In August 2006, Garcia and a crew that included his wife and two teenaged children headed to sea. In Japan, meanwhile, Iwasaki, digging through the Japanese Defense Ministry archives, discovered the Kano Maru’s log book, long lost due to a clerical filing error. It contained a chart with the coordinates of the encounter with the Grunion. This crucial find narrowed the search area from thousands of square miles to about 200, with a primary target area of just 20. Instead of searching a large house for a needle, the Aquila could now search, in effect, a single room.

For three days, the team scanned the ocean floor, at depths down to 6,000 feet, recording sonar images. One showed a crumpled tubular shape, lying on a slope 3,200 feet down. When John Abele showed the image to Ballard, the oceanographer cautioned him: “Don’t let your desire for this to be the right target fool you into thinking that it is.”

The image tantalized. There was something there. But was it the Grunion? Was it even a submarine? “At the very least,” Abele says, “it gave us something to go after.” The brothers wanted to know more, to see more. That meant a second search. And this time, Abele himself would go along.

As the ocean searches unfolded in remote Alaska, a parallel quest was taking place, led by a trio of fanatically dedicated women known as the sub ladies, operating in tandem in their suburban homes. In less than two years, Rhonda Raye, Vickie Rodgers and Mary Bentz—all relatives of men lost on Jim Abele’s boat—undertook to locate all of the sailors’ families.

The sub ladies had a precursor. After the Grunion vanished in 1942, Kay Abele had written letters of condolence to each crew family. Most wrote back, some many times. The letters, from wives and fiancées, from grieving parents, hint at anguish well beyond what the era’s decorum permitted to be spoken. “Mrs. Abele, I’ve let myself go all to pieces,” wrote one wife, six months after the ship’s disappearance. “Do you feel there is still hope? I just can’t make myself believe that all are gone.… Please forgive me if I upset you, but I can’t help myself.”

The memory of such pain in their own families spurred the sub ladies on. Bentz, whose uncle had died on the ship, recalls that when her father would talk about his brother, his eyes would fill with tears. “Until I was older and married, I didn’t realize how much my grandmother must have suffered, losing her son like that.” The Grunion project soon came to dominate Bentz’s life. “I became a junkie. Up early before dawn, up late at night. You could call it an obsession.”

The three women approached the challenge with dogged resourcefulness. “They used every tool imaginable,” Bruce Abele says, “plus some you’d never imagine.” In one typical search—for the family of the ship’s executive officer, Millener Thomas—Rodgers consulted genealogical charts and marriage records, Social Security death files, newspaper obituaries, probate records, telephone books. Discovering that Thomas’ widow had remarried, and that his son, Peter, had been adopted by his stepfather and renamed Peter Stephens, Rodgers wrote to everyone named Stephens in Allentown, Pa. One letter reached Peter Stephens’ daughter, who passed it on to him. Another family, returned to the Grunion fold.

I asked Bentz what it was like for Grunion families to receive a phone call out of the blue, after all these decades. “Sometimes people just weep,” she told me, when I called her home in Maryland. “This not-knowing—it’s been a part of the fabric of our lives for over 60 years.” One long-lost sister of a crew member was found living in a convent. Another search located two sisters given away for adoption as infants—unaware of each other’s existence. One of the Grunion sailors had had a child with a Filipino woman—a boy who, as a blond-haired, blue-eyed American citizen, spent the Japanese occupation hidden away in various houses in Manila.

The Grunion project was growing, gaining momentum in a very 21st-century way, as if to illustrate John Abele’s theories of crowdsourcing and the power of networks. A Web site included crew photos and a blog. Hobbyists from Israel to Brazil weighed in on military and technical issues. A Grunion mailing list swelled to many hundreds of names. In Japan, Iwasaki began locating families connected to the Kano Maru and to two sub-chaser boats the Grunion sank just days before its own sinking. He collected information from the families, telling the story from the Japanese side. “This project represents a model for collaboration in today’s world, ” John Abele would say later. “Aim a diverse set of minds at solving a problem, and it’s amazing what you can do.” Bentz, meanwhile, persuaded dozens of local newspapers all across America to run stories in communities where Grunion sailors had lived. Eventually, the sub ladies set themselves an ambitious deadline: by the time of the second search expedition, they would track down relatives of every single crew member.

Grunion's propeller guards, as found off the coast of Kiska Island

|

The second expedition took place in August 2007, a year after the initial search. In Massachusetts, a remote-operated vehicle, or ROV, equipped with five high-definition video cameras, was loaded onto a flatbed truck, driven to Seattle and shipped up to the Aleutians. Once more Garcia readied the Aquila and assembled his crew. John Abele flew in on his jet to Adak, a former Navy base, and made the 24-hour boat ride to Kiska Island.

Fifteen hundred miles from the Alaskan mainland, Kiska is a forbidding place, treeless and fogbound, guarded by a looming volcano. “It’s Lord of the Rings meets Nanook of the North,” Abele says. It is a place of primordial weather events: earthquakes with a magnitude of 9, volcanic eruptions and winds that routinely reach hurricane force. Garcia describes the conditions at sea as “horrible—some of the worst in the world.” In past trips, he’d seen waves smash the front of his boat in. “We’re talking waves that can split three-inch steel like an aluminum can.”

Garcia viewed the mission as highly quixotic. “I’ve done some oddball charters over the years,” he says. “But this was by far the most oddball.” Despite Abele’s optimism, doubters abounded. National Geographic agreed to send a writer along—then backed out, concluding it was a waste of time. David Gallo, an oceanographer who joined the crew, confessed that his Woods Hole colleagues rated the chances of finding the sub at “zero.” And on the Aquila, the crew was placing bets on how long it would take to find the sub—if they could find it at all.

A propeller and a dive plane, as seen underwater

|

The effort started inauspiciously. On Kiska, the wind was blowing 90 miles per hour, and all the team could do was hunker down in the harbor and wait. Abele was nervous. “My concern was that I’d be here two weeks. You’ve got a crane, you have to lift this ROV and put it over the side and you can’t do that if the seas are too rough.” For 36 hours they waited. Then, at dusk on the second day, conditions suddenly changed. “We looked out and said, ‘Holy cow, the sea just got calm,’” Abele recalls.

At 7 p.m., the Aquila set out to search the deep waters off Kiska. Weather reports indicated a massive low-pressure system headed their way, so speed was essential. Arriving at the target area at 9 p.m., the crew lowered the ROV and turned on the cameras. Almost immediately they saw a strange object. “It looked like kelp,” Abele says. “But then we got closer.”

It was the bow of a submarine—right away, on their first try. As the ROV moved around the stern, one image eerily duplicated a photo of the Grunion under construction at the Electric Boat shipyard in Connecticut.

“There she is,” John said quietly.

Looking into the sub's forward torpedo room from a break point

|

The team worked all night, steering the ROV around the wreck, taking hours of high-definition video. The Grunion was badly damaged: its deck had been sheared off, a 50-foot section of its bow was gone and the pressure tanks along the entire length of the submarine gaped open. It looked, a crew member remarked, as if someone had gone at the ship with a gigantic can opener. The crew on the Aquila saw no human remains, and Abele hadn’t expected any. At that depth in the calcium-poor water, he had learned, bones would have dissolved long ago.

Back on the East Coast, Mary Bentz woke before dawn to check the Grunion Web site. When she saw the post from Bruce Abele—“WE FOUND THE SUB!”—she burst into tears. Just days earlier, the sub ladies had tracked down relatives of the penultimate crewman on their list. Now only one remained, a seaman from Detroit named Byron Allan Traviss.

Bentz was determined to find Traviss’ family before the day was over. She called in to a popular Detroit talk show and broadcast a plea for information. “And lo and behold,” she recalls, “a woman in her kitchen hears the radio say something about Byron Traviss, and she calls in to the show and says, ‘Byron’s Purple Heart is hanging on my dining room wall!’” The woman in the kitchen was the wife of the crewman’s cousin. At last, the list was complete: on the same day the Grunion was found, the sub ladies had met their goal.

Out in Alaska, dawn broke, and the ROV was hauled back up onto the Aquila. From the side of the boat, Abele tossed wildflowers onto the sea above the Grunion. He collected a container of water, which he and his brothers would later siphon into 70 vials and package in commemorative cases, one for each family, with a photo of the Grunion and a short note: “The water from this vial comes from the Bering Sea just off the Aleutian island of Kiska. It was taken from over the resting place of the USS Grunion. It is a small memento of the gravesite of the crew and a symbol to honor their service and their sacrifice.”

The Grunion families met last year in Cleveland, where relatives tossed a carnation into Lake Erie for each lost crewman.

|

Fourteen months later, the Grunion families united in Cleveland at the memorial site of a sister sub, the USS Cod. Under a brilliant blue sky, 200 Grunion relatives, including two nonagenarian widows of the lost sailors, heard John Abele’s wife, Mary, an interfaith pastor, read an invocation from Psalm 107: “They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; These see the works of the Lord, and His wonders in the deep.”

Speakers offered tributes to the lost men and expressions of gratitude to the Abele family, including Kay, who died in 1975, and Brad, who died nine months after the sub was found. At a dinner the night before, Bentz had read a comment left on the Grunion blog: “Lt. Commander Mannert L. Abele’s contribution to his country is evident in his sons.”

The Abele brothers had served as stand-in captains, carrying on their father’s mission of responsibility for his crew, even as the Grunion project expanded in ways Jim Abele never could have anticipated. In Japan, Iwasaki had tracked down the 97-year-old widow of the commander of a sub chaser sunk by the Grunion. She and the Abeles would later exchange gifts and greetings: the survivors of old adversaries, joined now in a collaboration that honored each other’s losses and healed the enmities of history. “Such an effort of compassion and wisdom,” commented Bruce Abele, “makes me think there may be hope for this planet.”

In Cleveland, as the elegiac strains of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” played in the background, Mary Bentz read each crew member’s name aloud. From the deck of the Cod, family members tossed a carnation into Lake Erie for each crewman. The rifle cracks of a 21-gun salute resounded, and a trumpeter played “Taps” as the flowers floated on the surface of the water.

“I think Jim would be pleased to know we made this effort,” John Abele said later. “You know—‘Don’t worry, Dad. We’ll finish the job here.’”

On a breezy afternoon in February 2009, I went with John and Bruce to visit the house in Mystic, Conn., where they’d been living the last time they saw their father. A shingle structure with a big wraparound porch, it stands on a steep hill overlooking town; a little bit higher, and we could have seen five miles west to the Thames River, where the Grunion set sail that May day 67 years ago.

The current owners graciously showed the brothers around. John’s memories were few: a window seat, the ornate pattern of a lead-paned window in the living room. “Where was the Victory Garden?” he asked Bruce, as they stood on the porch. It was all so long ago.

This painting shows the condition of the Grunion in 2007. The artist, a retired submariner, believes that for the crew, the end came with merciful speed.

|

That night the two gave a talk to a packed auditorium at Mystic Seaport, presenting a video Bruce has assembled, The Search for the Grunion. The video included a detailed painting of the wreck by retired submariner Jim Christley, who has also contributed a systematic analysis of the sub’s sinking. Questions remain. Why did the Grunion broach, or rise to the surface, exposing itself to fire? How did a relatively minor hit from an eight-centimeter gun cause catastrophic damage? What caused the loss of depth control that led the sub to plunge beyond its crush depth and implode?

Christley was in the audience at Mystic, and he told me that for the crew, the end came with merciful speed. “They would have died instantaneously,” he said. “One minute you’re doing everything to save the boat, and the next minute it’s lights out. Your brain doesn’t even have time to register the fact that your body’s in trouble.”

After the video, the Abele brothers took questions. John was asked why he’d been willing to spend so much money—around $1 million, he’d told me—locating his father’s ship. On other occasions, I’d heard him answer this question with a brisk “Because we could!” Tonight, to an audience sprinkled with Navy veterans in their gray submariner’s vests, he gave a different response. “Fifty million people died in World War II,” he said. “Good people, on both sides. This was our way of remembering them.” Abele likes to describe the Grunion project as the intersection of two curves: the rising information curve created by the Internet and the falling demographic curve of American World War II veterans, who are currently falling victim, a thousand of them per day, to the silent artillery of time. You could see it in the auditorium that night—row after row of white-haired heads, the last of the Greatest Generation, revisiting its moment of glory and sacrifice via the Abeles and the story they have salvaged from the ocean floor.

There is a deeply bittersweet quality to the Grunion story, arising from the passage of time and the smiling faces of young men who remain frozen in their youth, even as those who loved them age and die. After the presentation, I talked with Betty Kockler, whose brother, Lawrence, was a torpedoman on the Grunion. Her entire adult life has been bracketed by the ship’s story: she was 13 when the ship disappeared and 78 when it was found. “I was stunned,” she told me. “To be sitting there after all these years and suddenly get a phone call?”

As a child she worshiped her brother, and she has thought of him, she said, “every single day of my life.” At the memorial ceremony in Ohio, she helped her other brother, now 90 and frail, carry the carnation all the way back to the stern of the ship—their brother had been an aft torpedoman — to cast it into the water. I asked what the moment was like. “It was beyond closure,” Kockler said, after a long pause. “It was something I can’t even describe.”

When John Abele describes the sequence of events that led to the Grunion’s discovery, he speaks of “a series of amazing improbables.” The plot is a tapestry of happenstances; pull one thread, and the whole thing may unravel. What if Richard Lane hadn’t decided to spend a dollar on the deck winch diagram? What if Bruce’s son’s girlfriend’s boss weren’t a World War II history buff? What if Yutaka Iwasaki hadn’t guessed where the Kano Maru logbook might be misfiled? Why did the wind die down so helpfully at Kiska, affording a 12-hour window between gales? Why, every time the crew of the Aquila lost track of Grunion, were they able to find it again immediately? And why was the water directly over the spot of the wreck preternaturally calm? “It was strange,” Kale Garcia said later. “As if we had some outside help.”

Person after person involved in the Grunion story agrees. Bruce Abele likens the search to “winning the lottery 13 times in a row.” Mary Bentz puts it bluntly: “It was divine intervention. I really believe that.” Even John Abele, whose career has been driven by a fervent faith in science, recognizes a point beyond which serendipity seems to betray a design, and the improbable becomes the imponderable. Sometimes, giving a presentation about the Grunion search, he’ll field a question about why he thinks his mission succeeded against such high odds. “Something wanted us to find that boat,” he’ll say—and, eyebrows raised, he’ll give a quick, questioning, grateful glance skyward.

![]() View more photos related to this story.

View more photos related to this story.

![]() Watch video of John Abele '59 discussing the search for the USS Grunion.

Watch video of John Abele '59 discussing the search for the USS Grunion.

![]() Read Abele family letters about the Grunion.

Read Abele family letters about the Grunion.

![]() Watch video of John Abele '59 discussing the USS Grunion at Reunion 2009.

Watch video of John Abele '59 discussing the USS Grunion at Reunion 2009.

Rand Richards Cooper ’80 is a fiction writer, essayist and critic. He wrote the feature “Ghost Writer,” about the life and death of John Stringer ’73, for the Winter 2008 Amherst magazine.

Photos courtesy Bruce and John Abele