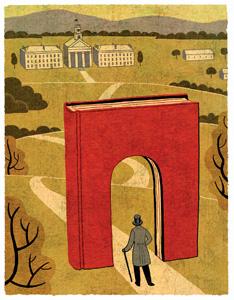

The Great Book Theft That Wasn't

A Williams grad traces the rise and endurance of a most persistent legend—the one that accuses the Fairest College of bibliolarceny.

By Dustin Griffin

|

One of the enduring legends about the ancient rivalry between Williams and Amherst is that when Zephaniah Swift Moore, second president of Williams College, decamped from Williamstown in September 1821 to become the first president of Amherst College, he took with him not only 15 students—one-fifth of the Williams student body of the day—but a number of books from the Williams library. Despite repeated efforts in the last 40 years to dismiss this story as nothing more than an amusing legend, it manages to persist, and it can still be heard repeated as scripture by alumni from either college. What explains the rise and endurance of the myth?

It’s an old tale, but not an ancient one. It’s not found in the standard printed histories of Williams College, not in Arthur Latham Perry’s Origins in Williamstown (1894) or his Williamstown and Williams College (1904). Leverett W. Spring says nothing of the theft in his 1893 article on “Williams College” in New England Magazine or his 1917 History of Williams College. And there’s nothing in William S. Tyler’s 1873 History of Amherst College (or his 1894 update), or in Claude M. Fuess’s Amherst, Story of a New England College (1935). Perry goes so far as to say in his 1904 book that “there was never any real or rational ground for a feeling, that has been traditionally kept up in Williamstown almost to the present time ... that somehow or other, by somebody or other, the older institution was wronged or worsted by the newer one.” Perry’s words suggest that by 1904 nobody was saying anything about book theft, but there was a feeling on the part of some, irrational perhaps, that there was something immoral or even illegal, or just wrong, about the events of 1821. In time just what was wrong would be revealed.

I don’t remember the story from my own student days at Williams in the early 1960s. But John Chandler thinks he might have heard it soon after arriving at Williams in 1955. And it was plainly in his mind when, as dean of faculty at Williams, he and Provost Joseph Kershaw made a field trip to Amherst’s newly opened Frost Library in late 1965 or 1966. Williams President Jack Sawyer, already thinking about how to remedy the perceived shortcomings of his college’s Stetson Library, had sent them east to take a look at a modern library that was regarded as a success. As Chandler tells the story now, he and Kershaw arrived unannounced and were spotted by somebody they knew who wanted to know why they were there. “We’ve come to retrieve our books” was their prompt—and joking—answer. They had evidently heard the tale and thought they would have some fun with it.

Where did the story come from? In his 1873 book Tyler reported that in September 1820, when the academy that would later become Amherst College opened for business, the entirety of the library was “contained in a single case scarcely six feet wide,” but also that by October 1821 there were 700 volumes in the Amherst College library. (Some bear the signature of President Moore himself, says Michael Kelly, current head of archives and special collections at Frost Library.) Was there a sudden accession of books just before October 1821, or had there been 700 volumes in the “single case”? This “single case” was perhaps a multi-shelf bookcase, and perhaps the books were slim volumes, though 700 books seems like rather a large number for even a tall bookcase. Nonetheless, Fuess, in his 1935 history of Amherst, resolves the matter by declaring that the single case held all 700 books. But documentary evidence is lacking: the first printed catalogue of the Amherst library, dated 1827, says nothing about the origin of the first books. At least one subsequent Amherst historian, F. Curtis Canfield, who gave a series of short informal chapel talks between 1946 and 1954 about the founding of Amherst, thought that the “single case” contained only 50 books—though he says nothing about bibliolarceny.

In 1965, when Frost Library opened, the history of libraries at Amherst would have been a matter of some interest. Perhaps somebody from that era remembered Canfield’s estimate (published in 1955) of 50 books and idly or mock-solemnly speculated that the rest of those first 700 books “must” have been stolen from Williams in 1821. Seeking to confirm that speculation, perhaps somebody else, just happening to browse in Calvin Durfee’s 1860 History of Williams College, came across the passage noting that some Williams students in 1821, preparing to join President Moore’s migration, voted at a meeting “to carry the library [of the two student literary societies] with them to Amherst.” And perhaps that somebody did not notice the continuation of the passage, reporting that a second resolution, to choose a committee to “carry this resolution into effect,” was defeated.

The sobersided Durfee was a member of the Williams Class of 1825 and thus an eyewitness to the events. Another contemporary witness was Parsons Cooke, Williams Class of 1822, who told the story of the student debate in his Recollections of Rev. E. D. Griffin (1855) and saw some humor in it. Cooke notes that in 1821 a “movement was made to transfer the library, which belonged to the literary societies in the college ... to Amherst College,” but suspects that the proposal began as a “joke,” or at least should be regarded as one. The “project,” he says, was “so decidedly juvenile, that, had not its opposers been equally juvenile, they would have made no resistance to it, but would have enjoyed the sport of seeing how far that joke could be carried.” He is amused that the students of the time apparently took it seriously, even solemnly:

The parties joined issue in regularly called meetings, to discuss the question, whether the public good did not require that one of the libraries appertaining to Williams College should be removed to Amherst. The debates, and the ruling points of order in those meetings, as they now rise in memory, are really laughable. Never was a meeting more in solemn earnest. Never were a body of men more penetrated with the feeling that the fate of the nation depended on their action.

“Suffice it to say,” Cooke concludes, “the books did not move.”

Whatever the source (and it seems unlikely that Durfee or Cooke had many readers in the 1960s), the story came to the attention of Amherst’s longtime Professor of English Theodore Baird. Shortly after his retirement in 1969, Baird wrote to Williams Librarian Lawrence Wikander about encountering the story, noting mischievously that he was disposed to believe it. Wikander checked the printed catalogues for the Williams library, published in 1812, 1821 and 1828, and found that none of the 1812 books was missing in either 1821 or 1828, which seemed to prove conclusively that no books were stolen in 1821. Baird wrote back somewhat sheepishly to say that he was persuaded. (The originals of Baird’s letters, and Wikander’s reply, dated Nov. 4, 1971, are found in the Williams College Archives).

It is doubtful that the correspondence was ever widely known. When Williams gave an honorary degree to Peter Pouncey at the 1985 commencement, President John Chandler read out a citation in praise of Amherst’s then-president, declaring that “this is not the day to cast doubts on the courage of Zephaniah Swift Moore, or to speculate about whether his luggage contained purloined books from the library of the abandoned college.” As Chandler now remembers it, the citation was heard with delight by the graduating seniors. But nobody, he thinks, “took the story as serious history.”

Wikander’s discovery might well have come to the attention of Craig Lewis, Williams ’41, who, in the late 1980s, was commissioned to produce a history of the college in celebration of its bicentennial. His Williams 1793-1993: A Pictorial History, published in 1993, is notably silent on the matter of the Theft.

But the story was not dead. In October 1994 Williams President Hank Payne, speaking at the induction of the new Amherst president, his old friend Tom Gerety, reported with mock-solemnity that he had “unearthed” the Baird-Wikander correspondence, and now declared that the alleged “dastardly larceny” never took place and thus that the “battle of the books” was over.

But it wasn’t over. Ten years later, in April 2004, Amherst Professor Rick Griffiths, then associate dean of the faculty, at an event celebrating the accession of the Amherst library’s millionth volume, made a few remarks about the library’s beginnings. “Both the Amherst and Williams archivists assure me that, contrary to a persistent but inaccurate rumor, the students who left Williams in 1821 to become Amherst’s first students did not bring books from the Williams library to start the college library collection at Amherst.”

Still the story endured. And it spread, passed from mouth to mouth, stimulated in particular by the loyal efforts of Dick Quinn, director of sports information for Williams, to provide colorful material for sportswriters on the occasion of a big Amherst-Williams game. Since at least the late 1990s he has incorporated zesty references (and mock-denunciations of President Moore as “The Defector”) to the story in his press releases. As the Williams-Amherst football game approached in November 2005, Williams Record reporter Julia Rominger ’06, her invention heated by the occasion, suggested that Moore took with him fully “half of Williams’ students, faculty and library books.” On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the first Williams-Amherst baseball game in the summer of 2009, Jim Briggs, Williams ’60, who managed the team representing Williams, was asked about the “defection” and was quoted on Yahoo Sports saying (perhaps tongue in cheek), “We’re sure [the decamping President Moore] took some of our library books, too.” Bloggers, trawling websites, keep the story alive.

Even the official Williams College website, in its brief biographies of its presidents, in effect gives the story continued life: “It is rumored that President Moore began the Amherst College library with books stolen from Williams, but there is no proof that this actually occurred.” Wikipedia regards the story as only a “legend” that remains “unsubstantiated,” an “apocryphal” tale told by Williams alumni, for which there is “no contemporaneous evidence,” but still calls it “plausible.” Other websites (e.g., Answers.com, New World Encyclopedia) recycle the story and probably find plenty of receptive readers.

But perhaps there’s another explanation for the endurance of the legend. Maybe the story of the book theft is now becoming part of the founding myth—one of the stories Williams fans need to tell and re-tell about how the rivalry between Williams and Amherst goes right back to the founding of Amherst itself, complete with a comic villain, the dastardly defector who sneaked off with books in his backpack. A myth for a postmodern world. And the Amherst fans can smile with satisfaction at the idea of successfully stealing books from the Williams Library decades before it became common for undergraduate pranksters to carry off some treasure from the campus of an archrival—or for Amherst students to carry off their own Sabrina.

It’s all a little theatrical, as if part of an operetta, with no consequences in the real world. Or no serious ones, anyway. In 1994, nearly 175 years after the Great Book Theft, Williams President Hank Payne told an audience at Amherst that he figured that, “at reasonable compound rates,” Amherst owed Williams “at least a million volumes.” And within a year or two the Williams College Mucho Macho Moo-cow Marching Band presented Amherst with a bill for $1.6 billion in library fines for overdue books.

Dustin Griffin, a 1965 graduate of Williams, is professor of English emeritus at New York University. He retired in 2009 after 40 years of full-time teaching. He is the author of a number of books on 18th-century English literature, including Swift and Pope: Satirists in Dialogue (Cambridge University Press, 2010). He lives in Williamstown, Mass.

Image by James Steinberg