In the very first issue of The New York Times, published on Sept. 18, 1851, the editors proclaimed that their conception of what counted as the news (that’s fit to print) would include the goings-on of the literary and publishing spheres: “We shall sometimes … take note of the books of the day—unravel their narrative into a newspaper column and give the public, whom we have taken in hand to serve, a running synopsis of their story.” In 1896, this coverage was promoted, or perhaps sequestered, to an insert to the paper, originally titled The New York Times Saturday Book Review Supplement and today known as The New York Times Book Review.

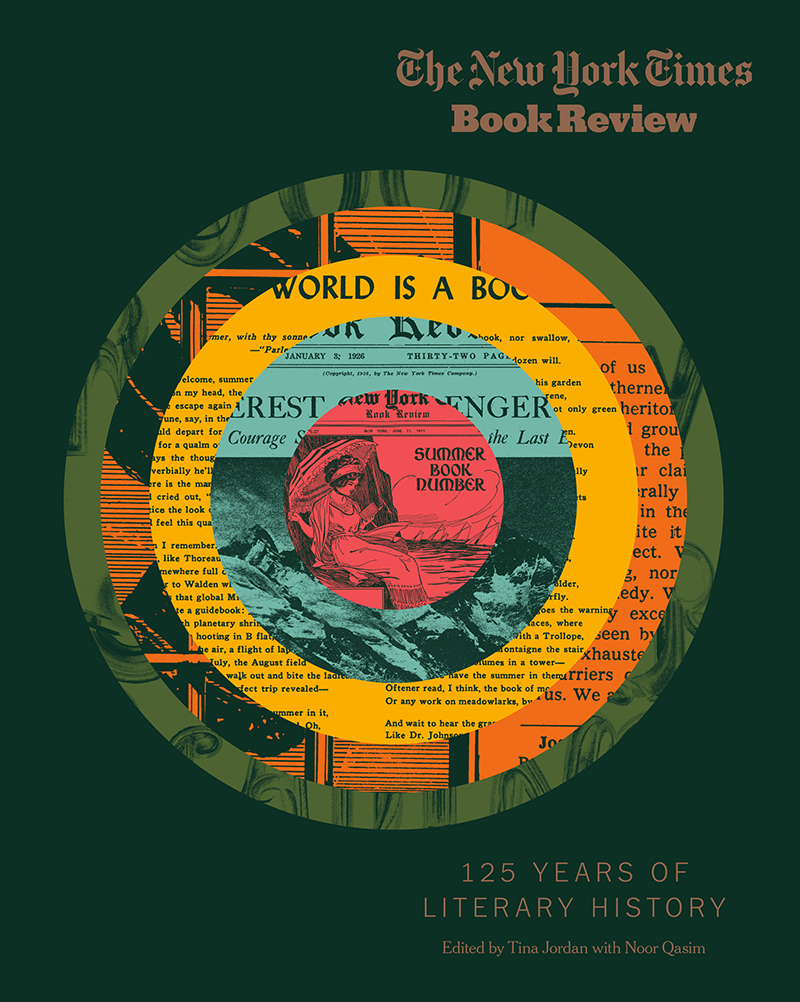

To celebrate the Book Review’s 125th birthday, editors Tina Jordan and Noor Qasim ’18 spelunked into the archives and emerged with a handsomely bound, coffee-table-ready book that compiles some of the most notable materials from the Book Review’s history. Reviews, profiles, interviews, advertisements and rare photographs (like Norman Mailer riding the Cyclone roller coaster on Coney Island) are presented in a manner that is a pleasure to flip around at random.

Plenty of big names grace these pages, as both reviewed and reviewer. To name a few of the highest-wattage pairings: Joan Didion on John Cheever, Tennessee Williams on Paul Bowles, Anatole Broyard on Ralph Ellison, Eudora Welty on E.B. White, and a personal favorite of mine, W.H. Auden on J.R.R. Tolkien (“by the time one has finished his book one knows the histories of the Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves and the landscape they inhabit as well as one knows one’s own childhood”).

Edited by Tina Jordan and Noor Qasim ’18

Penguin Random House

Interstitial letters to the editor reanimate the reviews as cultural moments rather than mere artifacts. “You feel like you’ve uncovered a treasure,” Qasim told me in an interview. Take the exchange between Joan Didion and Alfred Kazin, after Didion’s review of John Cheever’s Falconer. As Qasim told me: “Kazin is—I think rightfully—rather perturbed by the way Didion has characterized his reviews of Cheever.” So Kazin sends a letter to the editor: “She suggests that I do not wish to be honest in my reading. This is worse than outrageous—it is stupid.” Didion responds, simply, “Oh, come off it, Alfred.” To Qasim, “it’s the sort of grave and funny thing you’d overhear at a cocktail party, but it’s just there, in the pages of the Book Review.”

The cultural utility of a vicious pan is a matter of eternal debate, and in these pages, we see the waxing and waning of acceptable levels of vitriol. Writes John Leonard on fellow critic Dale Peck’s 2004 collection of knifings, Hatchet Jobs: “This isn’t criticism. It isn’t even performance art. It’s thuggee. However entertaining in small doses—we are none of us immune to malice, envy, schadenfreude, a prurient snuffle and a sucker punch—as a steady diet it’s worse for readers, writers and reviewers ... .”

Although I’m inclined to agree, one of the most interesting and entertaining pieces collected here is the withering and comprehensive annihilation, by Austrian American journalist William S. Schlamm, of the debut literary offering by one Mr. Hitler. On Mein Kampf, Schlamm wrote in 1943: “[The translator] should be put on the honor list of war casualties. … Here, for the first time, you get Hitler’s prose almost as unreadable in English as it is in German. … Confronted with a faithful translation of Hitler prose, any publisher or editor would ask, in disgust, if the young man was kidding. … This is the Moronic Evil, so shapeless and pre-spiritual that it defies articulation.”

The most significant value of 125 Years of Literary History, greater than the sum of its parts, is its timeline of how the Book Review has struggled at great pain to catch up with changing cultural and social mores. In an incisive original essay that opens the book, critic Parul Sehgal grapples with the Book Review’s preponderantly white male history. Commenting on critics who’d underappreciated the work of several marginalized writers, she writes: “To dismiss these reviews as mere fossils requires a series of awkward and dishonest contortions. Reviewers … might have handled the work of gay writers with tongs, but the public didn’t.”

How did working on the book change Qasim’s appreciation of the Book Review? “I dove into the archives with the expectation that the historical coverage would skew overwhelmingly toward the white, the male and the wealthy,” she told me. “And, of course, it does. But I was also intrigued to find instances in which the Book Review was surprisingly responsive to the concerns of the day, attentive to the interests of a diverse readership, and more expansive—for example, in reviewing untranslated books written in languages other than English—than it even is today. All this is to say that I found it refreshing to look back at literary history in this way, to examine all the ways the past can confirm one’s worst expectations, while also, at times, shifting or undermining them, pushing us toward a more complex reading of who we were then and, by extension, a fuller understanding of who we are now.”

Mancusi is a novelist and critic. His first novel, A Philosophy of Ruin, was published by HarperCollins in 2019.